Breeding Bird Atlases (BBA)

Find a Bird

Least Tern

Sternula antillarum

Local and likely increasing

Action/monitoring needed

Species of Special Concern

“And overhead the air was full of the graceful, flitting forms of this little ‘sea swallow,’ darting down at me with sharp cries of anxiety, or soaring far aloft until they were lost to sight in the ethereal blue of a cloudless sky.” – Arthur Cleveland Bent, Life Histories of North American Birds

The appropriately named Least Tern is the smallest of the tern species that breed in Massachusetts, but that in no way has stopped it from becoming big news. Its preference for nesting on sandy mainland beaches rather than the islands favored by many terns has brought the species into conflict with humanity time and time again. Currently sharing top conservation billing and some prime beach real estate with the Piping Plover, this listed Species of Special Concern is doing its best to hold on.

Historic Status

Alexander Wilson called the Least Tern the Lesser Tern, and the early ornithologists of Massachusetts knew it as the Silvery Tern, but by any name the Least Tern was a ”not uncommon” summer resident and breeder along the state coastline in the early and mid-1800s. Joel Asaph Allen called it, “Common along the coast in summer” in 1878, but when gunners employed by the millinery trade moved in the Least Tern suffered. The species gave up historic breeding grounds at Ipswich and other places, gradually retreating to a few, more southerly haunts. Edward Howe Forbush estimated that 300 birds remained in the breeding colonies on the Cape and Islands, on the South Shore, and South Coast, but by the 1930s Massachusetts State Ornithologist Joseph “Archie” Hagar estimated almost three times that many. Under full legal protection, the population in Massachusetts increased throughout the middle decades of the twentieth century.

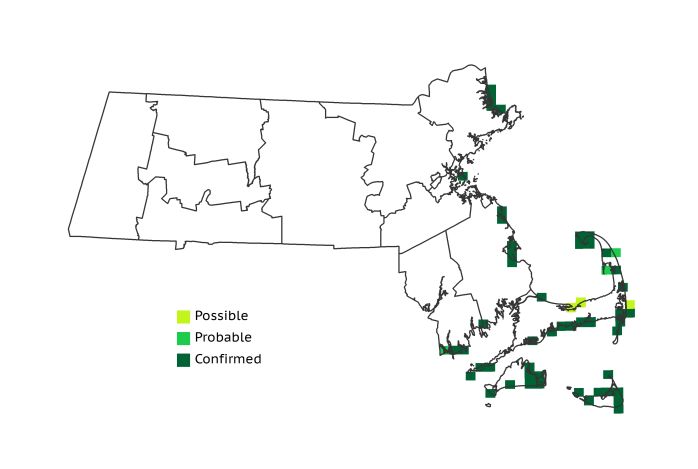

Atlas 1 Distribution

By the time of Atlas 1, the recovering Least Tern population was still not free of its conflicts with humans. The Least Tern’s preference for the same sandy beaches valued by humans for recreation has always created a rocky relationship between the terns and humans in many areas. However, it has not been a problem at protected sites like the Parker River National Wildlife Refuge on Plum Island in the Coastal Plains, where Least Terns nested in several adjacent blocks. The Boston Basin had a single, somewhat surprising block in the heart of Boston Harbor, and the Bristol/Narragansett Lowlands also hosted breeding Least Terns around the southwestern coast. Cape Cod and the Islands were unquestionably the places favored by Least Terns, accounting for 43 of 54 occupied blocks, many of which were located on popular tourist beaches.

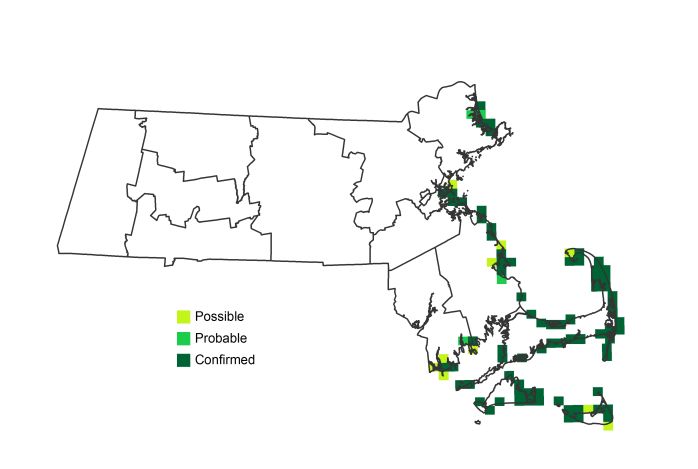

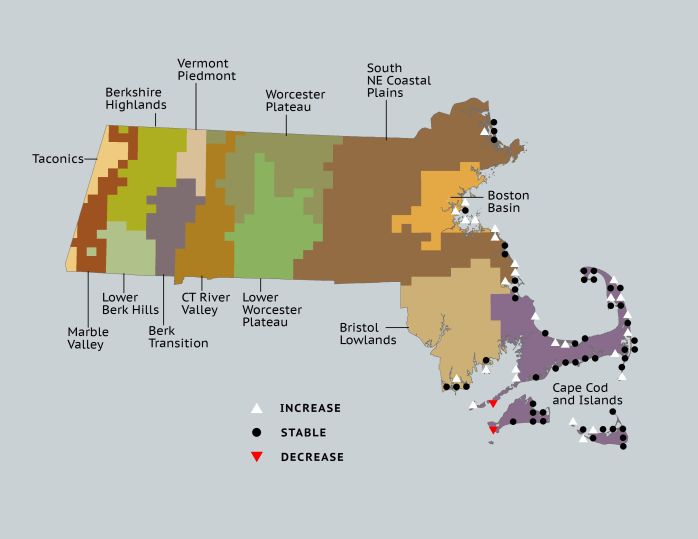

Atlas 2 Distribution and Change

Least Tern block occupancy jumped to 89 blocks during Atlas 2. The species’ persistence was remarkable – they were found in a total of 50 blocks during Atlas 1 and persisted in at least 50 of those blocks during Atlas 2. With new additional blocks, and very few losses, Least Terns have seemingly gained ground. More precise estimates of the change in this species’ breeding status (see Note below) support an increasing abundance in the state, although there is considerable variability in this population.

Atlas 1 Map

Atlas 2 Map

Atlas Change Map

Ecoregion Data

Atlas 1 | Atlas 2 | Change | ||||||

Ecoregion | # Blocks | % Blocks | % of Range | # Blocks | % Blocks | % of Range | Change in # Blocks | Change in % Blocks |

Taconic Mountains | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

Marble Valleys/Housatonic Valley | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

Berkshire Highlands | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

Lower Berkshire Hills | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

Vermont Piedmont | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

Berkshire Transition | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

Connecticut River Valley | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

Worcester Plateau | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

Lower Worcester Plateau | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

S. New England Coastal Plains and Hills | 7 | 2.6 | 12.7 | 15 | 5.3 | 16.9 | 6 | 2.7 |

Boston Basin | 1 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 5 | 8.9 | 5.6 | 4 | 7.3 |

Bristol and Narragansett Lowlands | 4 | 3.8 | 7.3 | 8 | 7.0 | 9.0 | 2 | 2.0 |

Cape Cod and Islands | 43 | 31.6 | 78.2 | 61 | 42.4 | 68.5 | 14 | 11.7 |

Statewide Total | 55 | 5.7 | 100.0 | 89 | 8.6 | 100.0 | 26 | 3.1 |

Notes

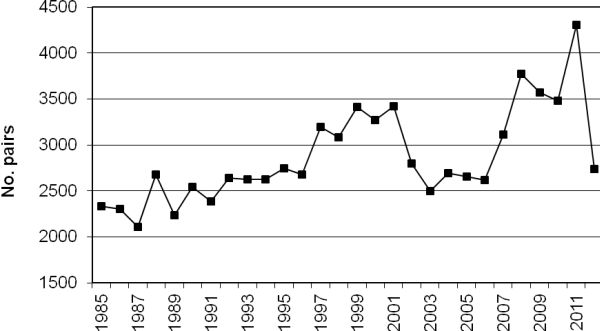

The challenges of using traditional Atlas methods to assess changes in colonial nesting species are well known. Single colonies are easy to miss, and even if a colony is reduced by 90%, the species is still recorded as breeding in the block. Estimates from counting pairs or nests are far more precise than Atlas field methods. This species is broadly distributed, and trends of their footprint do mirror the abundance trends noted in official surveys, although Least Terns are notoriously variable in numbers. The Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program of the Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife maintains the official counts for this species and other beach nesting birds (see graph below of the number of Least Tern pairs since 1985). The growth of this species footprint and abundance has been accomplished with intense management at nesting sites that includes symbolic fencing, some beach closures, and a corps of docents to help educate beachgoers about the sensitivity of beach nesting birds to disturbance. Due to their similar nesting habitat preferences, Least Terns and Piping Plovers have often been managed together. While the population of Least Terns has increased, the species will always be at risk from human disturbance and predation, and therefore these measures of protection must be retained for the population to continue in Massachusetts.