Find a Bird

Bald Eagle

Haliaeetus leucocephalus

Local and strongly increasing

Endangered Species

“Great men are like eagles, and build their nest on some lofty solitude.” – Arthur Schopenhauer

Despite Benjamin Franklin’s insistence that the Wild Turkey would have been a more appropriate choice, the Bald Eagle has been the symbol of the United States of America since its inception and it has symbolized courage, strength, ferocity, and freedom through the years. In reality, though, Bald Eagles often prefer to scavenge carrion when it is available rather than catch their own prey. What they cannot scavenge, they may steal from other birds. When they cannot scavenge or steal, eagles hunt for live prey, most often fish, but they will also feed on a wide variety of other animals as well. Like Ospreys, this species owes both its demise and recovery to the same source: humans.

Historic Status

Bald Eagles, like many other raptors, saw better days before the arrival of European settlers to the Northeast. Although habitat degradation undoubtedly spearheaded their near demise, hunting, trapping, and poisoning also contributed to their population downfall in the state. “In my experience the Bald Eagle,” wrote Edward Howe Forbush in 1927, “... is more sinned against than sinning.” By the late 1800s, breeding in the state was sporadic and dispersed, from Cheshire in the Berkshires, to Snake Pond in Sandwich on Cape Cod (Veit & Petersen 1993).

Atlas 1 Distribution

Since the Snake Pond birds apparently spent their last breeding season in Massachusetts in 1905 (Veit & Petersen 1993), no Bald Eagles were definitively found breeding in Massachusetts for decades. Still recovering from the crippling blow dealt by DDT, Bald Eagles were totally absent from Massachusetts as breeding birds during the first Atlas period.

Atlas 2 Distribution and Change

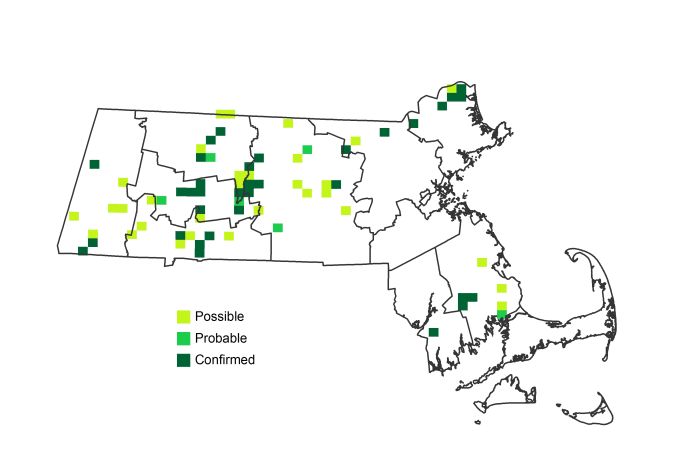

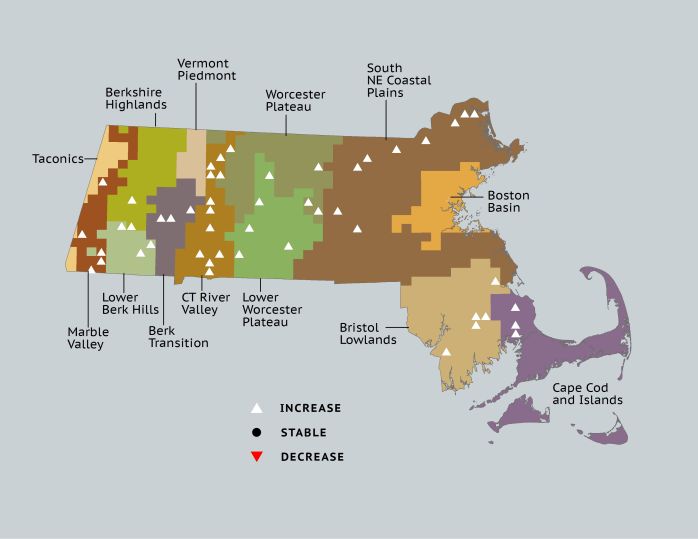

By the time of Atlas 2, Bald Eagles were soaring over Massachusetts in growing numbers. Our national bird was Confirmed breeding at several locations in the Marble Valleys, and occasionally they were reported in the Berkshire Highlands, Lower Berkshire Hills, and Berkshire Transition. Ultimately, the rushing waters of the Connecticut River Valley proved productive for the Bald Eagle population, with this region alone accounting for over a quarter of all occupied blocks statewide. The Quabbin region in the Lower Worcester Plateau was also a major concentration area for Bald Eagles, which were otherwise sparsely distributed in central Massachusetts. The Coastal Plains also had a number of breeding Bald Eagles, mostly along the Merrimack River in the northern part of the ecoregion. Although no eagles were found in the Boston Basin, the Bristol/Narragansett Lowlands had several breeding pairs, and a few eagles even ranged out to Cape Cod.

Atlas 1 Map

Atlas 2 Map

Atlas Change Map

Ecoregion Data

Atlas 1 | Atlas 2 | Change | ||||||

Ecoregion | # Blocks | % Blocks | % of Range | # Blocks | % Blocks | % of Range | Change in # Blocks | Change in % Blocks |

Taconic Mountains | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

Marble Valleys/Housatonic Valley | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 5 | 12.8 | 7.0 | 5 | 12.8 |

Berkshire Highlands | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2 | 3.6 | 2.8 | 2 | 3.8 |

Lower Berkshire Hills | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3 | 9.7 | 4.2 | 3 | 11.1 |

Vermont Piedmont | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

Berkshire Transition | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3 | 7.5 | 4.2 | 3 | 9.7 |

Connecticut River Valley | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 18 | 27.7 | 25.4 | 12 | 25.0 |

Worcester Plateau | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 8 | 9.1 | 11.3 | 3 | 6.3 |

Lower Worcester Plateau | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 11 | 13.8 | 15.5 | 5 | 9.3 |

S. New England Coastal Plains and Hills | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 13 | 4.6 | 18.3 | 9 | 4.0 |

Boston Basin | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

Bristol and Narragansett Lowlands | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 5 | 4.4 | 7.0 | 5 | 5.0 |

Cape Cod and Islands | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3 | 2.1 | 4.2 | 3 | 2.5 |

Statewide Total | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 71 | 6.8 | 100.0 | 50 | 6.0 |

Notes

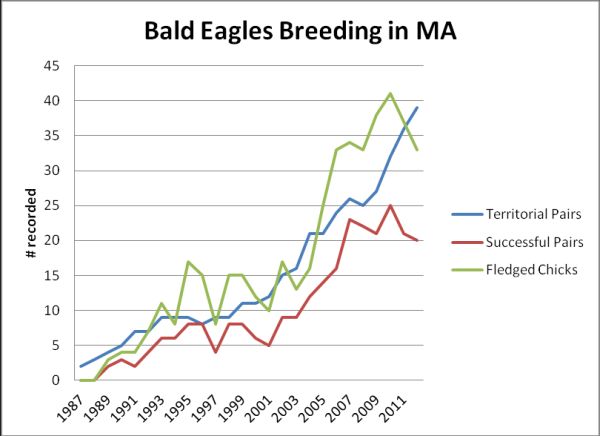

Although Massachusetts’ native eagles were entirely extirpated by the middle of the twentieth century, they breed in the Commonwealth today thanks to a hacking program instituted in the 1980s. The Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife, together with the US Fish & Wildlife Service, took young eagles from Michigan and Canada and placed them in artificial nesting towers at Quabbin Reservoir. From 1982 through 1986, young eagles were reared and fledged at the Quabbin towers, and the first mature birds returned to breed in 1989 (Veit & Petersen 1993). From there, the population has continued to grow.Included below are the results of annual surveys for nesting Bald Eagles by the Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program of the Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife.