Find a Bird - BBA1

Breeding Bird Atlas 1 Species Accounts

Northern Flicker

Colaptes auratus

Egg Dates

April 29 to June 20

Number of Broods

one; may re-lay if first attempt fails.

The Northern Flicker has one of the most extensive ranges of any North American bird. It is a common breeder in all sections of Massachusetts from the Berkshires to Cape Cod and the Islands. Although it can be found nesting in regions of extensive deciduous or mixed forest, the flicker prefers areas where stands of trees are interspersed with open habitats. It has adapted well to civilization, breeding readily in orchards, shade trees, woodlots, and city parks and seeking much of its food on lawns, fields, pastures, and golf courses.

Spring migration occurs mainly during April. At this season, most of the resident breeding birds arrive at the same time that migrants are passing northward. The birds announce their arrival with a loud, ringing wick-wick-wick-wick call. Other common vocalizations include a klee-yer or ti-err call and a wicker-wicker-wicker or yucka-yucka-yucka series, used frequently at or near the nest site. Both sexes also produce a loud drumming sound by pecking rapidly at a tree limb, the walls of the nest cavity, or even a metal roof, pipe, or insulation box.

One or more courting males may follow a female from tree to tree, creeping and dodging around the trunk and branches. During display, in addition to vocalizing, they bow, nod, turn the head from side to side, and open the wings to expose the yellow linings (hence the former name of Yellow-shafted Flicker). Flickers nest in cavities that they excavate in live or dead trees, stumps, or posts. Both sexes work for one or two weeks at the task of drilling a new chamber, although old sites may be reused once any debris that has accumulated has been cleared out. Typical cavities are 2 to 4 inches in diameter, 10 to 36 inches deep, and are located from 2 to 60 feet above the ground. Of 6 Massachusetts nests, 1 was in a dead trunk, 1 in a decaying oak, and the others in deciduous trees (maple, elm, and Red Oak). Heights ranged from 7 to 30 feet (CNR). Flickers will also use nest boxes that have been designed for them. Occasionally, the birds will nest in unusual sites. There are historical records of eggs placed on hay in a barn in Lynnfield (the birds first having drilled a hole through the wall to enter) and a set of five eggs was discovered on the ground at the edge of a sand road in a Pitch Pine forest on Cape Cod (ACB).

The three to ten (usually at least five) white eggs are laid on a bed of wood chips that have been left in the bottom of the cavity. Clutch sizes in 4 Massachusetts nests were four, five, six, and seven, respectively (CNR). In another sample of state nests, 5 contained six eggs and 1 contained eight eggs (DKW). If robbed of eggs before her clutch is complete, the female flicker will continue to lay, and there are records of over seventy eggs being produced by a single bird. When a complete clutch is lost, the bird will produce a new set after digging deeper in the cavity or moving to a new site. Squirrels may prey on eggs and small nestlings, and starlings are serious and persistent competitors for nest cavities. Although two broods are reared in portions of the range, this does not appear to be the usual situation in Massachusetts.

Both sexes share in the incubation duties, alternating at intervals during the day. The male remains in the cavity, covering the eggs at night, and the female retires to a separate hole. Hatching occurs after 11 to 12 days, and the nestlings, initially naked and totally helpless, sprawl at the bottom of the cavity for another 11 days. By 17 days of age, they can cling to the sides of the hollow and at three weeks are able to climb up to the entrance hole to be fed. Initially, the youngsters are brooded by the adults on the same schedule as that followed during incubation, with the off-duty bird returning to feed the young by regurgitation. After two weeks, the male roosts with the young but does not cover them, and at the end of the third week he does not spend the night with them, nor does either adult remain in the cavity during the day. Fledging occurs when the young are 25 to 28 days old. During the last few days before making their first flights, the young spend a good deal of time climbing about outside the nest hole. In Massachusetts, most young have fledged by the end of June.

Little information has been recorded about postfledging events. The adults tend the young while they begin to forage on their own. Old and young generally spend the night in cavities, but they may cling to tree trunks or the sides of buildings. When the young leave the nest, they are garbed in a juvenal plumage similar to that of the adults, except at this stage both sexes have dark mustachioed markings. They attain the adult plumage during a molt from June to October, and at the same time the adults have a complete molt.

The diet of the Northern Flicker is approximately 61 percent animal matter and 39 percent plant material. Ants are a favorite food, along with a variety of other insects and invertebrates. These woodpeckers are commonly observed foraging on the ground, well out in the open, as they seek out anthills. Various seeds and fruits, including those of cherry and Black Gum, are also taken.

The flicker is often listed as a permanent resident because some individuals are present at all times of the year. However, most birds move to the southern United States for the winter. Fall migration peaks from late September through October. During this time, the residents depart and large numbers of northern migrants pass through. Those that remain in Massachusetts are found most commonly in the southeastern sections, although there are regular records from interior regions as well. During severe weather, flickers seek shelter in thickets and stands of conifers.

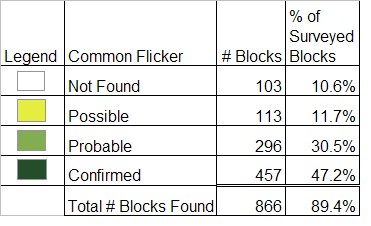

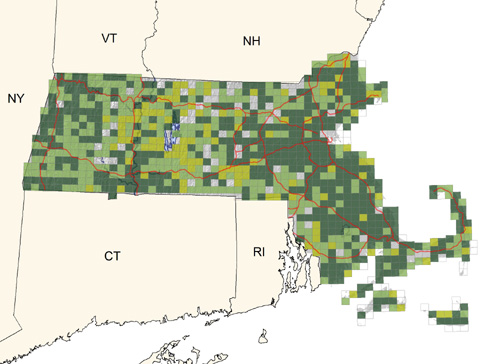

Map Legend and Data Summary

Atlas 1 data collected from 1975-1979

Note: common throughout the state wherever trees are present

W. Roger Meservey