Find a Bird - BBA1

Breeding Bird Atlas 1 Species Accounts

Mourning Dove

Zenaida macroura

Egg Dates

late March to early August

Number of Broods

two

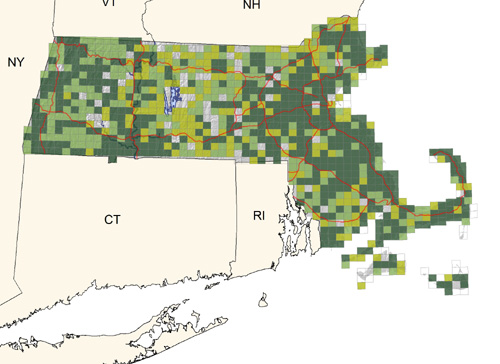

According to Forbush, the Mourning Dove “had decreased so much in numbers in the early part of the Twentieth Century that Massachusetts led the way in 1908 by giving it perpetual protection under the law, to save it from extirpation.” By the 1920s, the species had increased and was an “irregular resident in the eastern counties,” and the population has continued to grow. During the Atlas period, the Mourning Dove was a common nester in all sections of the state. It is most abundant in the vicinity of open fields and is absent only from the most heavily forested areas. As the numbers increased, the pressure to allow hunting of Mourning Doves in Massachusetts has also intensified; however, even though the species is now listed as a game bird in over 30 states, the Commonwealth has not agreed to permit shooting of this smaller edition of the Passenger Pigeon.

Although the Mourning Dove is a permanent resident in Massachusetts, the numbers are considerably smaller in winter than they are during and after the breeding season. Migrants generally begin to return in late February or early March and are detected both by the calling of the males and sightings of flocks feeding in plowed fields. The song, given most frequently at dawn or dusk, coah-coo-coo-coo, is often mistaken by novices for the soft hooting of an owl. Doves produce several low growling calls, which are heard only at close range, and, like many members of the pigeon family, they have a nest call. When flushed from the ground, trowel-shaped tails flared, they can startle an observer with a twittering made by the wings.

Mourning Doves are believed to mate for life, and the male’s courtship ritual is vigorous. With nest feathers ruffled, wings drooping, and tail cocked, he stamps his feet and struts around, much like a turkey, to win the female’s attention. In addition, he will fly high into the air, making a loud noise by hitting his wings together over his back. When he reaches a height of 100 feet or so, he returns to earth in a series of circular sweeps on stiffened outspread wings.

Mourning doves build the simplest of nests, untidy but efficient, fairly flat and airy. Both sexes work together to weave course sticks and twigs onto the bough of a conifer, the heavier branches of a deciduous tree, or, rarely, on top of an old nest of another species. Twenty-eight Massachusetts nests were located as follows: White and Red pines (10 nests); Blue Spruce (3 nests); Red Cedar (2 nests); apple, plum, White Oak, Slippery Elm, and Weeping Willow (9 nests); English Ivy (1 nest); vine (1 nest); window ledge (1 nest); old robin nest (1 nest) (CNR). The habitats for 26 of these nests were as follows: wooded area (9 nests), suburban or yard (12 nests), orchard (2 nests), dune thicket (2 nests), tree in field (1 nest) (CNR). Heights ranged from 5 feet to 40 feet, with an average of 15.6 feet (CNR).

The clutch size is nearly always two eggs, and this held true for 8 state nests that were examined (CNR). The male incubates for much of the day and is relieved by his mate for the remainder as well as the night shift. Hatching after 14 to 15 days, the young are fed a secretion called pigeon’s milk, produced in the crop of both parents, by regurgitation. Increasing amounts of seeds are mixed in as the young mature. Both adults take turns brooding the young until they are well feathered. Fledging occurs in about two weeks, and the immatures continue to receive some feedings for a brief time as they attain independence. Brood sizes for 18 state nests were one young (4 nests), two young (14 nests) (CNR). Once one set of young has fledged, the pair takes a week or more to court, build another nest (occasionally the same nest is used again), and produce a second clutch of eggs. The breeding period is extended, with eggs reported in the state from late March to early August, nestlings from April 17 to September 16 (CNR), and recently fledged young from May 15 to mid-September (TC, BOEM). The peak period of nesting in the Commonwealth is from late May through June, with 99 percent of all nests initiated before July 30 (BOEM).

Adults have a complete molt after nesting is finished. Mourning Doves begin forming loose flocks, feeding, and roosting communally as early as mid-July, with numbers of birds in these flocks building during August. Migration begins in September, and most that are going to leave have departed for the southeastern United States by December. Depending on the severity of the early winter, the numbers overwintering in Massachusetts can vary. Overall, the wintering population seems to have increased, possibly as a result of the growing popularity of winter bird feeding. However, Mourning Doves have some difficulty withstanding a severe New England winter.

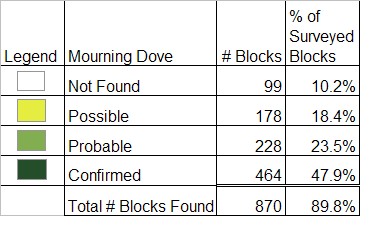

Map Legend and Data Summary

Atlas 1 data collected from 1975-1979

Note: common and widespread in a wide variety of habitats

Thomas L. Carrolan