Find a Bird - BBA1

Breeding Bird Atlas 1 Species Accounts

Roseate Tern

Sterna dougallii

State Status

Endangered

Federal Status

Endangered

Egg Dates

May 12 to August 18

Number of Broods

one; may re-lay if first attempt fails.

Ever since the first historical records in the 1870s, the state has harbored more than half the Roseate Terns breeding in North America. Roseate Terns in Massachusetts were reduced by plume hunting to about 2,000 pairs in the 1890s, but increased under protection to a peak of about 5,000 pairs in the 1930s. They then decreased again to about 1,600 pairs in 1978 but subsequently have stabilized or slightly increased. Most of the remaining birds nest in one densely packed colony on Bird Island in Marion. The concentration of so much of the population on one small island makes it very vulnerable, and the Roseate Tern has been designated as an endangered species in the state.

Roseate Terns start to arrive on the Cape and Islands in early May. They feed along the coast and in bays and tidal inlets, preferring clear waters where tide rips or predatory fish bring Sand Eels and other bait fish to within 2 feet of the surface. They dive deeply into the water from heights of up to 40 feet. They nest on sandy or rocky islands, where they prefer areas that are more densely vegetated than those selected by other terns.

The Roseate Tern can be distinguished by its sharp, disyllabic call, chi-vik, which is uttered during feeding and courtship display. In response to intruders on the breeding colony, it gives a harsh alarm call, aaach, like tearing cloth, or a melodious klew. Roseate Terns have a spectacular aerial courtship display, in which groups of three to eight birds spiral up to heights of 100 to 600 feet and then descend in pairs in long, weaving glides. They rarely rest on the water but spend much time bathing in small groups in shallow water near shore. Loafing birds collect in flocks on beaches or sandflats, often with Common Terns.

Roseate Terns usually lay one or two eggs in a scrape concealed under a clump of Dunegrass or other plants. Most eggs are laid in late May to mid-June, but some younger birds do not start to lay until late June or July. After the eggs hatch, in 23 to 25 days, the chicks hide in long tunnels under the vegetation and emerge only to be fed. The parents alternate in incubating the eggs, brooding and guarding the chicks, and bringing food. The chicks are fed on small fish, which are often caught several miles from the colony; some birds from Bird Island commute regularly to fishing grounds around Woods Hole, 10 to 12 miles away. Roseate Terns attack gulls and other birds that intrude into their colonies but do not attack humans or other mammals. They invariably nest in mixed colonies with Common Terns and appear to benefit from the aggressive behavior of that species.

The chicks fledge at 22 to 28 days of age during July and early August but continue to be fed by their parents for at least six weeks until they learn to fish for themselves. If two chicks are raised, the family breaks up at fledging and 1 parent tends each chick. Average fledging success in Massachusetts (late 1960s to early 1980s) was about one chick per pair. After breeding, most birds move to the outer shores of Cape Cod and the Islands, where flocks of up to 5,000 occur at favored places such as Monomoy and Nauset. There they feed mostly on Sand Eels or other schooling fish that are abundant within a few miles of the shore.

Roseate Terns start to migrate south in late August, and most have departed by late September. Banding has shown that they fly directly south over the Atlantic Ocean, passing through the West Indies in September and October. The winter quarters extend along the north coast of South America from Colombia to northern Brazil. Young birds remain there for about 18 months. They usually migrate north to the breeding area at the age of two, but most do not breed until they are three or four years old. In recent years, Roseate Terns have been killed for human food in their winter quarters, especially on the coast of Guyana. This was probably the main reason for their rapid decline during the 1960s and 1970s, although encroachment by Herring Gulls onto the breeding colonies, predation, and toxic chemicals probably also contributed.

The Roseate Tern is listed as federally endangered in Massachusetts.

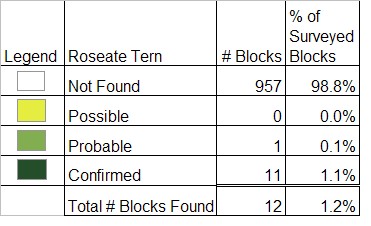

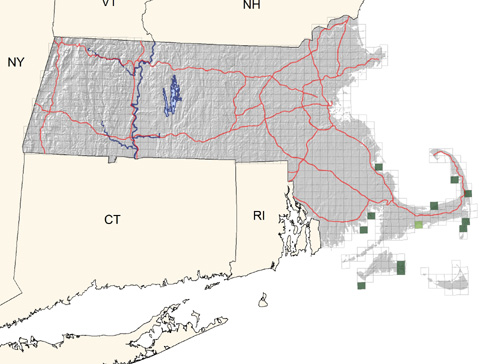

Map Legend and Data Summary

Atlas 1 data collected from 1975-1979

Note: local on southeast coast, common only at Bird Island; population currently stable

Ian C. T. Nisbet