Find a Bird - BBA1

Breeding Bird Atlas 1 Species Accounts

Ring-necked Duck

Aythya collaris

Egg Dates

May

Number of Broods

one; may re-lay if first attempt fails.

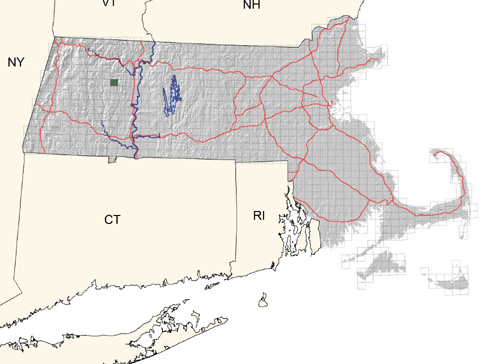

Prior to 1930, the Ring-necked Duck nested to the north and west of New England and eastern Canada and was seldom observed in Massachusetts, even during migration. Forbush considered it the “rarest duck in the Northeast.” Between 1930 and 1935, it became increasingly common as a spring and fall migrant. In 1936, nesting was recorded in Pennsylvania and Maine, and in subsequent years a breeding population was established throughout eastern Canada and northern New England. Ring-necked Ducks became most numerous in Maine, New Brunswick, Ontario, and Quebec. They are best known in Massachusetts as common migrants, but there have been a few breeding records. Nesting occurred in Concord in 1947 and 1951, and during the Atlas period there was a single confirmation from Ashfield.

Inappropriately named for the inconspicuous chestnut-colored band around the neck, the bird should be called “Ring-billed Duck” for the prominent white ring on its bluish gray bill. It is a fairly quiet species. The male utters weak whistling notes, and the female makes faint purring sounds. In display, the drake raises his crown feathers, holds his head erect, and then throws it back. Pair formation may begin in the fall and winter but usually occurs during the spring.

Spring migrants generally appear in Massachusetts during March, with numbers peaking in April. Small groups regularly linger until late May or even early June, but virtually all of these individuals eventually depart. The females tend to return to their natal areas to nest, and pairs tolerate one another so hens may nest in closer proximity than do many other duck species. Preferred nesting habitats are swamps, bogs, or small ponds with marshy borders. The habitat selected by the pair that bred in 1977 during the Atlas period was a Beaver pond surrounded by dead trees and marsh grasses. Other species nesting at the pond included the Canada Goose and Hooded Merganser. Suspicions about the possibility of breeding were raised when two pairs of Ring-necked Ducks were recorded there during May and June of 1976. In 1978, two pairs again were observed on the pond in June, but no nesting activities were discovered. Since that time, the Beavers have disappeared and the water level has become too low for nesting waterfowl.

The nest is a hollow lined with grass, other plant materials, and down. It is always near or surrounded by water and may be concealed in tussocks or clumps of marsh plants. Island nests may have vegetation ramps to make access easier for the hen. In Maine, the laying of eggs usually starts the second week of May and peaks around May 23 (range May 1 to August 16). Clutch size ranges from six to fourteen eggs (average nine). If the first nest is destroyed, the hen often will lay a slightly smaller second clutch. Males abandon their mates toward the end of the 26- to 27-day incubation period. A Massachusetts nest in an island plant tussock at a pond in Concord contained twelve eggs on May 22. In Maine, most eggs hatch from late June to early July, but small young are encountered throughout August. The Atlas record was of a hen escorting nine downy, golden ducklings on July 9, 1977. It is believed that six of these were reared successfully.

The hens brood the young when they are small and usually remain with their ducklings while they molt and replace their flight feathers. The young begin feeding on invertebrates, switching to plant foods as they mature. They fledge at six to eight weeks of age.

Ring-necked Ducks that have nested in northern states and Canada begin arriving in small flocks in Massachusetts by early October. They feed and rest on inland ponds, avoiding salt water, before moving on to wintering grounds in the southern states, Mexico, Central America, and the West Indies. Most have departed by December, but, depending on the severity of the season, a few may remain in the state.

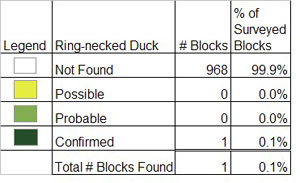

Map Legend and Data Summary

Atlas 1 data collected from 1975-1979

Note: rare in wooded swamps of western Massachusetts

Helen C. Bates and W. Roger Meservey