Find a Bird - BBA1

Breeding Bird Atlas 1 Species Accounts

Evening Grosbeak

Coccothraustes vespertinus

Egg Dates

not available

Number of Broods

one; possibly sometimes two

Formerly unknown in the Northeast, the Evening Grosbeak was once a resident of the boreal forests of northwestern Canada, with other populations occurring in the western mountains south to Arizona and Mexico. About 150 years ago, the species began a slow expansion eastward. The pattern was one of winter invasions, following which some of the birds would remain behind to nest after the flocks had departed again in the spring for the Northwest. The reasons for the development of this west-to-east migration pattern are not totally clear, but it has been suggested that two factors may have played roles. First, the widespread planting of Box Elder on prairie farms provided a favorite food in the form of seeds and buds as well as a “bridge” to the eastern forests; and, second, after the 1930s, feeding stations stocked with sunflower seeds, another favored food, supplied a reliable winter food source.

The Evening Grosbeak was not known east of the Great Lakes until 1854, when it was reported in Toronto. After 1875, it began to increase in the northern midwestern states. An invasion during the winter of 1886-1887 brought the birds into Ontario and New York. The first Massachusetts records occurred during the winter of 1889-1890, when grosbeaks reached New England in numbers and ranged from southeastern Massachusetts to Orono, Maine. Small numbers subsequently were reported in winter in New England until 1910-1911, when there was another big flight. From 1920 on, the species has appeared every winter in Massachusetts in variable numbers. By 1940 there were scattered summer records for New England and some reports of fledged young in the northern states. The eastward expansion continued, with the birds reaching the Canadian Maritimes by the mid-1960s. Nesting is now regular in the three northern New England states.

A Massachusetts nesting record at Northfield in 1937 cited by Bagg and Eliot (1937) is generally regarded as inconclusive. The first accepted state nesting followed a winter (1957-1958) when grosbeaks arrived in the Northeast in record high numbers. After the masses had departed, reports of lingerers or summerers came in during May and June, and, finally in July 1958, a female was observed feeding fledglings in Hadley.

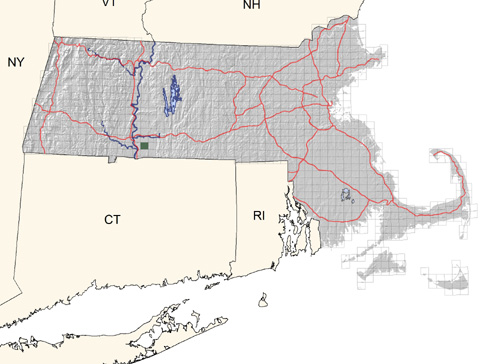

The situation has changed little in the intervening years. Scattered summer reports, mainly from the northern and western parts of the state, follow winter records. The species remains elusive while breeding. During the Atlas period there was only one confirmation (1978), when the female of a pair was observed nest building in West Springfield. Unfortunately, the birds departed without continuing further with the nesting cycle. No one has yet found a nest with eggs or young in the state. Reports of adults feeding fledglings have come from Berkshire County (e.g., Pittsfield, 1980, 1990) and northern Worcester County (e.g., Petersham, 1990; Princeton, 1991).

Winter residents and migrants from farther south depart for more western and northern breeding grounds from March to early May, with lingerers remaining well into the latter month. Flocks move from one feeding station to another during migration, but they gradually become less interested in sunflower seeds as natural foods such as buds, seeds, and maple sap become available. Since the Evening Grosbeak is a rare nester in Massachusetts, by the end of May only scattered pairs and small groups are observed. The birds are highly gregarious outside the breeding season and apparently gather in smaller flocks to forage at times, even when nesting. In spite of their name, they are most active during the morning and are observed infrequently after early afternoon. This trait is especially noticeable in the winter, when the birds visit feeders, arriving early and bickering with one another and other species but leaving the area well before the rest.

Evening Grosbeaks have a variety of calls. While feeding, the birds may be silent, except for the biting and cracking sound of their beaks, or may keep up a peet peet kreek peet kreek peet peet or a tchew-tchew-tchew. The main contact call, a shrill pete or p-teer, is heard from birds flying overhead or from members of a scattered feeding flock. The seldom-heard song of the male is described as a pleasant chip-chip-chou-wee. There are also scolding, alarm, and begging calls.

During courtship, one or both partners may bow. The male feeds the female and displays by fanning the tail and spreading and quivering the wings. The nest, constructed by the female, is built loosely of twigs, with some moss and lichen added. It may be in either a conifer or deciduous tree, usually well concealed, from 6 to 70 feet up. The West Springfield nest was in a spruce (Forster). Typical clutches consist of three or four (range two to five) eggs. The female incubates for 12 to 14 days, during which time she is fed by the male. Both sexes feed the young, which fledge after 13 to 14 days. Parental care continues even after the young have begun feeding on their own. Adults feed insects to the nestlings and typically macerate the prey before delivering it. This stains their greenish yellow bills with a brown color, a clue for those attempting to confirm nesting. Adults feeding from one to three fledglings have been reported in the state from July 5 to July 16 (Shaub 1959, BOEM, Shampang).

While captive birds have been known to raise two broods and there have been late records of adults feeding fledglings in other parts of the range, it is not known to what extent the species is double brooded in our area. Adults have a complete molt after nesting, and juveniles attain their winter plumage by a partial molt. Nothing is known about the movements of local birds after nesting. Typically, they bring their young to a summer bird feeder for a time and then disappear from the area. Fall migrants appear in September, with heavier flights during the next two months. Some of these birds remain to winter while others move on to more southern states. In some years, the main flights do not arrive until winter is well advanced. Numbers present in Massachusetts vary greatly from year to year as well as from locale to locale.

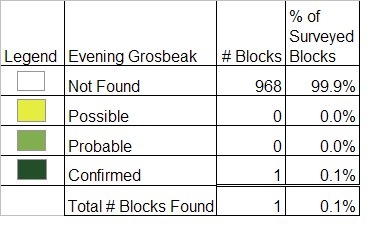

Map Legend and Data Summary

Atlas 1 data collected from 1975-1979

Note: rare and local in western Massachusetts; apparently increasing recently

W. Roger Meservey