Breeding Bird Atlases (BBA)

Find a Bird - BBA1

Breeding Bird Atlas 1 Species Accounts

Baltimore Oriole

Icterus galbula

Egg Dates

May 23 to July 4

Number of Broods

one; may renest if first attempt fails.

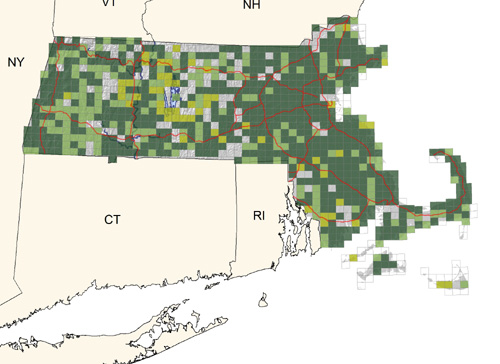

Historically called the Baltimore Oriole, this bird was renamed the Northern Oriole when it was found to interbreed with the Bullock’s Oriole in a zone of overlap in the Great Plains, thus relegating the two distinctive forms to one species. More recently, however, the species has once again been “split.” Regardless of which name it is known by, this brilliantly colored bird is common and widespread throughout the state. It is found wherever large trees are mixed with open spaces, such as farms, roadsides, parks, and suburban neighborhoods, and has a decided preference for riparian situations. It is absent only from extensive coniferous areas of the higher elevations of the state.

Except for the occasional early individual, Northern Orioles normally arrive during the first week of May. The first wave seems to occur almost simultaneously, or within a few days, across the state; later birds, mostly immatures, continue to appear throughout the remainder of the month. The musical, whistled song draws attention to the orange and black males as they establish territories in the sparse foliage of the trees. Females may arrive at the same time, or slightly later. The male courts the female with song and a bowing display with partially spread wings and tail. Males give a distinctive hoolee call, and both sexes produce various rattling calls and a loud chatter of alarm.

Nest construction commences in mid-May and has been observed in Massachusetts from May 14 to June 14 (CNR). The familiar pendulous nest is built hanging from the drooping tips of branches from 6 to 90 feet above the ground. Heights of 27 state nests ranged from 12 to 75 feet, with an average of 30 feet (CNR). In Massachusetts, 33 nests were located in the following tree species: maple (8 nests), apple (3 nests), Red Oak (3 nests), elm (7 nests), poplar (2 nests), White Ash (4 nests), Sycamore (1 nest), Choke Cherry (1 nest), willow (1 nest), Black Locust (1 nest), and pine (2 nests) (CNR, Meservey). Sites varied from urban parks and suburban and rural yards and orchards to various wood edges. Nests are woven in 4 to 8 days entirely by the female. A variety of plant fibers are used for the outside of the nest, and it is lined with hair, plant down, and other soft materials. Increasingly, artificially made materials such as string, fishing line, fiberglass, and plastic are found incorporated into nests.

By the end of May, four to six variegated eggs are laid. Clutch sizes for 3 Massachusetts nests were four eggs each (DKW). Incubation is performed mostly by the female, but it is believed that the male sometimes shares in the duties; the incubation period is 12 to 14 days. Nestlings remain in the nest for two weeks and are tended by both parents. During this time, the adults are aggressive in defense of the young. Nestlings have been reported in Massachusetts from June 4 to July 18 (CNR). Just before and immediately after fledging, the incessant and monotonous tee-dee-dee, tee-dee-dee food-begging calls of the ever-hungry youngsters are a familiar sound of the early summer. Fledglings have been observed in the state from June 19 to July 15 (CNR). Brood sizes at the times of fledging for 14 state nests were one young (1 nest), two young (4 nests), three young (4 nests), four young (4 nests), five young (1 nest) (CNR, Meservey). One brood is raised each season, but orioles may renest if the first attempt fails.

Once the young become indepen- dent and the begging calls cease, orioles seem to disappear. During much of July, they are seldom seen and rarely heard. During this period, adults and young un- dergo a molt and frequent dense vegetation, often near water, where wild berries are ripening. About the beginning of August, the familiar chattering call of orioles is heard once again. The shortened daylight also triggers another period of muted singing. By mid-August, the first orioles have begun to head south, and by late September all but a few stragglers are gone. Most Baltimore Orioles winter from central Mexico to northern South America, although some remain in the southern United States and the Caribbean. A few misguided lingerers may attempt to overwinter, but, even with the help afforded by bird feeders, few survive.

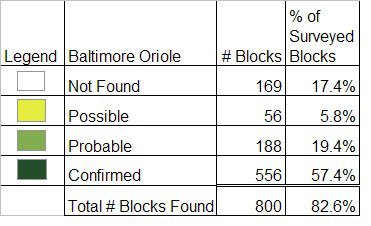

Map Legend and Data Summary

Atlas 1 data collected from 1975-1979

Note: fairly common in deciduous woodlands, in open wooded areas, and among shade trees throughout state

Mark Pokras