Find a Bird - BBA1

Breeding Bird Atlas 1 Species Accounts

Dark-eyed Junco

Junco hyemalis

Egg Dates

late May to July 26

Number of Broods

one or two

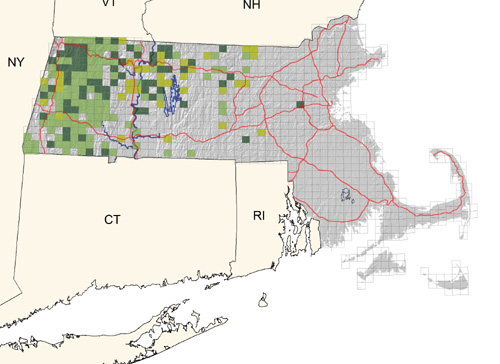

Even though it commonly nests in openings in coniferous and mixed woodlands and in brushy thickets of overgrown fields in the higher elevations of the western parts of the state, the junco is more familiar to Massachusetts residents as a winter visitor than as a breeding bird. It also breeds casually eastward through Worcester County into Middlesex County. In Forbush’s time, the species was commoner in southern Middlesex County than it is today, and it occurred sparingly in all of the other mainland eastern counties, but these populations have now all but disappeared.

In late March, migrants that have wintered farther south begin to arrive, augmenting the local winter population, which then forsakes feeders and moves to brushy fields and forest edges. The twittering conversational notes heard in winter flocks are then accompanied by song. Northward movement peaks in mid-April, and by early May summer residents have arrived on their breeding grounds. Birds that wintered locally are often among the last to depart.

The junco’s trilling song sounds like that of a melodious Chipping Sparrow but is highly variable among individuals. Males frequently sing from elevated perches, and the song period extends through late July. A twittering, warbling song is also occasionally heard. There are several call notes used in different contexts. The most familiar are a tack or smack scolding note, a tit-tit-tit location call and a tchet, tchet or bzzz of alarm.

Male juncos display by hopping on the ground near a female with the wings drooped and the tail fanned to show the white outer feathers. Nests are near or on the ground in some type of forest opening, often hidden under a fallen branch; sometimes they are on steep slopes. Two nests from Wendell were located as follows: 1 on bare ground mostly under a rock in a newly dug area, 1 on the ground in vegetation half under a fallen log (CNR). Occasionally, nests are placed in unusual situations. For example, Forbush reported a Townsend nest that was built in the corner of a narrow shelf inside a woodshed.

The female takes up to 12 days to make the nest, which is lined with very fine grass and hairlike roots. The three to five eggs are incubated by the female for 11 to 13 days. Both parents feed the young and the female broods them for up to 7 days, at which time their feathers begin to show. They leave the nest in about 12 days. The juveniles are partly dependent on the adults for food for three weeks. Often there is a second nesting in late June or July.

For the first few weeks out of the nest, the young bear little resemblance to the adults because in juvenal plumage they are dark brown and heavily streaked both above and below. Young male juncos molt into a plumage similar to that of the adult male while the immature female plumage is like that of the adult female but more strongly tinged with reddish brown. Adults have a complete molt in the fall.

There is little specific nesting data for the Commonwealth. In eastern Massachusetts, a male and nest were discovered on June 3, and the adults were observed carrying food during June (BOEM). One of the Wendell nests held three eggs on June 12 and four eggs on June 14, but by June 18 a predator destroyed the eggs. The second Wendell nest was being constructed on July 7. Four eggs were laid between July 10 and July 13. Three young hatched on July 26, but the nestlings were dead from exposure to heavy rains on August 3 (CNR). On June 25 in the Huntington-Chester area, 2 male juncos were each observed being accompanied on their territories by one large fledgling, and a third male was caring for two juveniles. All 3 were singing intermittently. The females were presumably occupied with a second nest (Meservey, Blodget).

The fall migration begins in mid- to late September, peaks in mid-October (when migrating flocks of juncos occasionally number in the hundreds), and ends about Thanksgiving. Dark-eyed Juncos have an extensive winter range that includes most of the eastern United States, but the center of winter abundance is in the Southeast. It is interesting to note that males tend to winter in the northern part of the range while females are more common in the south. Not surprisingly, in Massachusetts about 70 percent of the wintering juncos are males.

When snow covers the ground, small junco flocks move from weedy fields to feeders, where they are often found in the company of chickadees, nuthatches, finches, or American Tree Sparrows. Juncos are always present in winter, especially at lower altitudes, but their numbers vary from year to year. Occasionally, severe winter weather seems to reduce wintering populations.

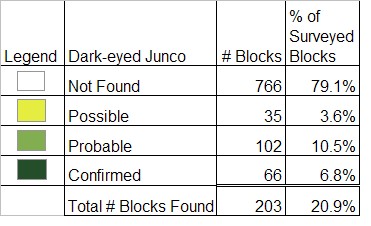

Map Legend and Data Summary

Atlas 1 data collected from 1975-1979

Note: fairly common in open areas of coniferous and mixed woodlands of hill country; rare in eastern Massachusetts

Robert P. Fox