Find a Bird - BBA1

Breeding Bird Atlas 1 Species Accounts

Cooper's Hawk

Accipiter cooperii

Egg Dates

late March to June 11

Number of Broods

one; may re-lay if first attempt fails.

The history of the Cooper’s Hawk in Massachusetts has been marked by dramatic changes in its population levels. Formerly present throughout the state, it was a fairly common breeder until the turn of the century, apparently reaching its peak of abundance during the late 1800s. Because the Cooper’s Hawk will nest in small groves, forest patches, or partially cut forest as well as in more extensive woodlands, it has adapted readily to the changing conditions associated with the spread of agriculture.

Any species that competes with humans is not regarded favorably, and the Cooper’s Hawk is no exception. A predator of game birds, many types of songbirds, and occasionally poultry, it won few, if any, friends, and was inevitably the victim of widespread shooting and trapping until the early part of the twentieth century. After 1900, it began a steady decline, with midcentury habitat destruction and pesticides adding to the bird’s problems. The fact that the species diminished from being a common to an uncommon spring and fall migrant was indicative that this trend was occurring throughout the Northeast.

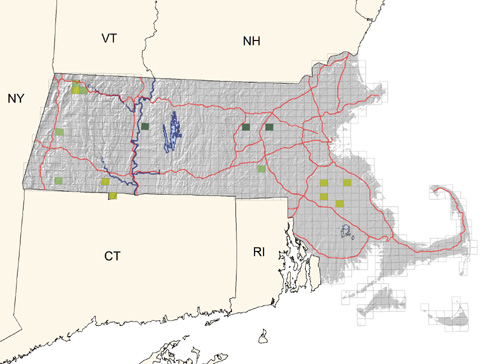

By the 1970s, the status of the Cooper’s Hawk was reduced to that of a rare and local breeder. The secretive nature of nesting Cooper’s Hawks and the extensive areas of suitable habitat in some regions made censusing difficult. During the survey, breeding was confirmed from only three stations, one each in Middlesex, Worcester, and Franklin counties. The species occurs in greatest numbers in Berkshire County, where it undoubtedly nests, though this is not confirmed. The presence of birds at other locales suggests that the species probably breeds more widely than is generally believed. Since the Atlas survey, the Cooper’s Hawk has been “confirmed” at a number of sites and is considered “probable” at several others.

The spring migration period extends from mid-March to mid-May, with resident birds generally arriving prior to or during early April. In Massachusetts, nests are frequently placed in conifers, especially White Pine (2 nests) or Eastern Hemlock (1 nest), but may also be built in oaks or maples, from 20 to 65 feet high. Sometimes the nest of another species will be appropriated or a previous nest will be reoccupied, but most commonly both sexes work in constructing a new nest each year. Small sticks are used for the framework, and a lining of bark, moss, grass, or leaves is added later. From two to six eggs may be produced, with four (1 nest) or five (1 nest) being the usual clutch. Incubation, which lasts from 21 to 24 days, begins with the first egg, resulting in young of different ages being in the nest. Both sexes incubate, but the female does the larger share. At a nest in Stow, five eggs hatched from April 20 to April 27 (Olmstead). Hatching at a Charlton nest occurred around May 24, and three out of four eggs in a Lancaster nest hatched in early June (TC). Nestlings remain in the nest from 21 to 25 days. The young at the Charlton nest fledged about June 17, and two were still with the parents on July 13.

The behavior of the adults at the nest is variable. At one Worcester County nest, the male took to the air and gave the cac-cac-cac warning call if disturbed. Once the young had hatched, he became more aggressive and would circle low, perching close to an intruder and calling loudly. The female nearly always disappeared into the woods, but on one occasion she did make a sweeping attack. At a second nest, both birds were much more retiring.

Food items include small mammals, grouse, ducks, poultry, small birds, snakes, frogs, and insects, but young in the nest are fed mostly birds. The young have a high shrill call. Newly fledged birds may return to the nest to be fed, and parental care continues until the young have mastered the powers of flight and have learned to hunt. By this time, family groups may have moved some distance from the nest site. Three Massachusetts records of adults with fledged young range from July 11 to July 24. Young birds wear their brown juvenal plumage through their first winter and begin to acquire the blue-gray feathers of the adult in spring. Adults have a complete molt in the late summer.

The fall migration period lasts from late August to early November. During this time, the resident birds depart and migrants from the north pass southward. Most Cooper’s Hawks winter in the southern United States, Mexico, and northern Central America, but a few remain farther north. The species is uncommon but increasingly regular during the winter in Massachusetts.

The Cooper’s Hawk is listed as a species of special concern in Massachusetts.

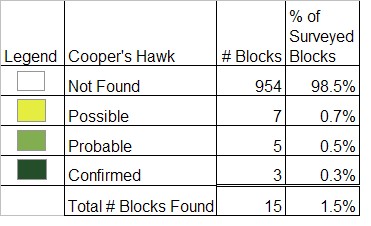

Map Legend and Data Summary

Atlas 1 data collected from 1975-1979

Note: rare in mixed or deciduous woodlands; dramatic recent increase

W. Roger Meservey