Find a Bird - BBA1

Breeding Bird Atlas 1 Species Accounts

European Starling

Sturnus vulgaris

Egg Dates

early April to July

Number of Broods

one or two

Perhaps no other species of bird in Massachusetts is more widespread or familiar than the European Starling. It is not universally admired and may, in fact, be held in public contempt more than any other bird. The starling was reportedly first introduced in Cincinnati, Ohio, in 1872. From then until 1900, at least ten additional attempts at introduction were tried, including two in Massachusetts: Worcester (1884) and Springfield (1897). The first apparently successful introductions were in New York City’s Central Park in 1890 and 1891.

Charles W. Townsend reported the first Essex County starling in 1908, and the species was first seen in the Concord region by Brewster in 1913. Beginning about 1920, there was a dramatic increase that continued unabated, and today the starling is widespread and abundant throughout most of inhabited North America in a wide variety of habitats. Currently, there are only a few locations in Massachusetts where it might conceivably not breed or be seen, such as dense woodlands.

The breeding chronology of resident birds is more subtle and prolonged than for migrant species from the south. One sign of approaching spring is a change in the bill color from dusky to yellow. The white-spotted winter plumage is transformed through wear into a shiny black with iridescent highlights on the head and body. In late February or early March, the winter flocks and small groups begin to disperse, and mated pairs start to explore nesting sites. At this time, the males become vocal, the song being little more than a varied series of squeaks, whistles, and rattles. However, the starling is greatly underappreciated as a mimic. Birdsongs that are frequently imitated tend to be the ones with simple, distinct phrases, such as those of the Eastern Meadowlark, Eastern Wood-Pewee, Killdeer, Eastern Phoebe, and Red-tailed Hawk. Also diagnostic in the song is the so-called “wolf whistle.” The alarm calls, rapid chatters and rasping notes, are a sure indication of the presence of a predator or intruder. Young birds utter harsh, grating sounds.

Nest building may commence in early April, with most nests underway by late in the month. The nest site is almost any suitably sized cavity, either constructed by humans or natural. Old woodpecker holes and the rotted eaves of ill-kept houses offer excellent nest sites. There is some competition with native species for cavities, and the starling has been considered a major factor in the decline of the Eastern Bluebird. Twelve state nests were located as follows: holes or nooks in buildings (5 nests); nest box (2 nests); cavity in tree, including elm and Sugar Maple (5 nests). Heights ranged from 8 to 33 feet, with an average of 19 feet (CNR). The nest cavity is rather casually filled with grasses and occasional twigs and is often lined with feathers.

A clutch of four to six white, pale blue, or greenish eggs is typical. Clutch sizes for 2 state nests were four eggs each (CNR). Both sexes share in the approximately 12-day incubation period and in feeding the young. At some nests, the females were observed to assume the greater role in caring for the nestlings. Once the young have hatched, their constant begging for food reveals the location of the nest. Brood sizes for 4 state nests were two young (1 nest), three young (2 nests), four young (1 nest) (CNR). The young remain in the nest for about three weeks and can fly well once they depart. Sometimes the young fledge prematurely, perhaps due in part to the heavy parasite infestation typical of the nests. There is some variation in the breeding cycle, but in general in Massachusetts the young of the first brood begin to fledge in mid-May, with large numbers appearing by the end of the month into early June. Second-brood young fledge during July and sometimes during early August (EHF, CNR). Once fledged, the young are a distinctive uniform gray-brown. Both immatures and adults congregate on lawns, short grass fields, and especially mown hay fields, where they often associate with blackbirds.

As summer progresses, the feeding flocks increase in size as second broods augment the numbers. At this time, flocks can be seen in the early evening flying to communal roosts, which they share with robins and blackbirds. These summer roosts are usually established in a grove of trees, either coniferous or deciduous. Sizable concentrations of nesting starlings can develop into a public nuisance when they become established in residential communities because the associated noise and droppings can create a very unpleasant situation.

With the approach of fall and the dropping of leaves, the roosting flocks tend to concentrate in coniferous forests and marshes, and under large highway bridges in the greater Boston area. Large compact flocks often frequent coastal marshes in autumn and are sometimes seen twisting and turning in unison in a manner similar to shorebirds. During the winter, the roosting flocks gather in larger numbers in fewer locations. Starlings will roost in downtown Boston behind signs and on ledges of older buildings. Abandoned buildings or warehouses will often host thousands of starlings in a roost. Perhaps the best-known roost is the Fore River Bridge in Quincy, where estimates of a hundred thousand or more are routine.

Although it is difficult to ascertain with a species as abun-dant as the European Starling, it is likely that many adults are year- round residents. Most immatures move south of New England in the winter, but there is no well-defined migratory movement. Forbush noted in 1925 that, with the approach of severe weather, numbers of starlings move south, but this is not evident today.

The ecological amplitude of starlings must be admired, and it is a major contributing factor in their success in this country. They can be seen hawking through the air for insects like a swallow or flycatcher, feeding on berries in fall and winter like robins and waxwings, or gleaning agricultural fields like blackbirds. Further evidence of their adaptability is the way they crowd just ahead of a bulldozer at a dump, or they ignore trucks and cars whizzing past them as they feed on highway median strips. Lastly, it should be noted that starlings are directly beneficial to suburban homeowners because they frequently feed on grubs found in lawns.

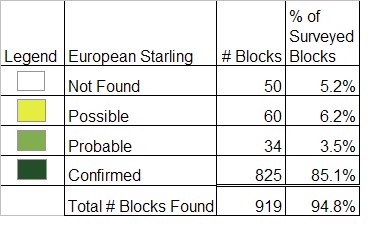

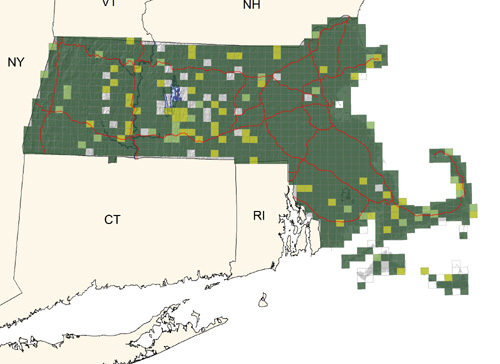

Map Legend and Data Summary

Atlas 1 data collected from 1975-1979

Note: very common throughout state in all but the most wooded habitats

Richard A. Forster