Find a Bird - BBA1

Breeding Bird Atlas 1 Species Accounts

Eastern Bluebird

Sialia sialis

Egg Dates

April 1 to August 7

Number of Broods

two; rarely three

The Eastern Bluebird became a common species during the historical period when settlers cleared the forest and created fields and orchards. During the twentieth century, bluebird populations in the Northeast declined by about 90 percent due to a combination of factors. Changing land uses and habitat destruction severely reduced the number of nest sites, and there was severe competition for the remaining cavities from native bird species as well as the alien House Sparrow and European Starling. Adverse weather, pesticides, and a decline of the winter food supply further added to the bird’s problems. However, since the 1970s, the bluebird has made a promising comeback as a result of more effective conservation and the establishment of bluebird trails with specially designed nest boxes.

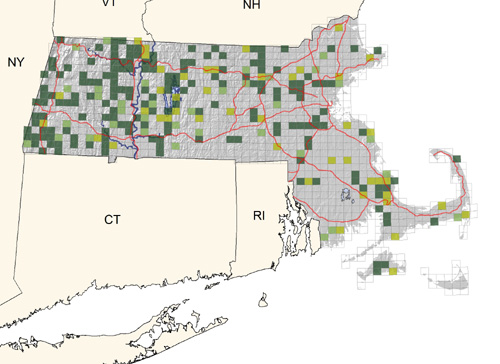

During the Atlas period, the bluebird was most common in rural areas of central and western Massachusetts and in southeastern portions of the state, where frequent forest fires help maintain suitable habitat requirements. Limited breeding also occurred in Essex County, the outer Cape, and Martha’s Vineyard, but not on Nantucket.

The first spring migrants usually appear in the middle of March, but arrival may continue well into April, depending upon weather conditions. By mid-April, most of the residents are well established on territory. The preferred nesting habitats—open areas with scattered trees where the ground is not covered with tall undergrowth—include farmland, orchards, open woodlands, swamps, pastures, golf courses, large lawns, country cemeteries, and military reservations.

The bluebird’s song is a rich, musical, warbling cheuerly-cheuerly, often repeated, and is basically an extension of the common chur-lee call note. Vocalization is most intense shortly after males arrive and begin to establish territories a few days in advance of the females. Calls are given frequently in flight. The alarm note is a chatter. Courtship is a thing of gentle beauty, with the male hovering before the female or perching near her and singing. It may be brief or last as much as a week before pairing occurs. The male locates a suitable nesting cavity, but the female makes the final choice of a site. Bluebirds are very territorial because a pair must maintain an area with an adequate food supply to rear the young.

Eastern Bluebirds are cavity nesters, utilizing natural tree cavities, old woodpecker holes in trees and fence posts, and suitable bird boxes. Heights of 44 Massachusetts nests in bird houses ranged from 3 to 10 feet, and heights of 2 natural deciduous cavities were 10 feet and 20 feet, respectively (CNR). The highest recorded state nest was at 35 feet in an old woodpecker hole in a power line pole (Meservey). In 4 or 5 days, the female builds a nest of fine dried grasses or pine needles. Bluebirds generally lay four or five short, oval, pale blue (occasionally white) eggs. Each successive clutch in a season tends to average one egg less than the previous one. Clutch sizes for 35 state nests were two eggs, possibly incomplete clutches (2 nests), three eggs (2 nests), four eggs (12 nests), five eggs (17 nests), six eggs (2 nests) (CNR). The female incubates for approximately 14 days, and the young remain in the nest for about 18 days before fledging.

Both parents feed the nestlings and remove fecal sacs. In one sample of state nests, nestlings were recorded from May 17 to August 12 and fledged young from June 4 to July 28 (CNR), and, in a second sample, nestlings were observed from April 18 to August 14 and fledglings from May 4 to August 31. Brood sizes in 34 Massachusetts nests were two young (3 nests), three young (4 nests), four young (16 nests), five young (9 nests), six young (2 nests) (CNR).

Two broods are generally raised in a season, and the male feeds the first-brood fledglings while the female prepares a new nest for the next brood. Juveniles stay together with their parents for the rest of the summer. Occasionally, first-brood siblings will act as helpers, feeding the second-brood nestlings. Most late broods are out of the nests by the end of August. Third broods are rare but do occur in Massachusetts, in which case young fledglings may be seen in September.

Bluebirds are primarily insectivorous. Two-thirds or more of their diet consists of a wide variety of insects, captured as the birds drop to the ground from exposed perches. Less frequently, they seize insects on the wing. From late summer and autumn into winter, berries become increasingly important food items.

Flocks of bluebirds will migrate south in October, the departure depending on weather and food supply. Most have gone by November. A few remain on Cape Cod and Martha’s Vineyard and at a few inland sites, but most bluebirds winter in the central and southern United States.

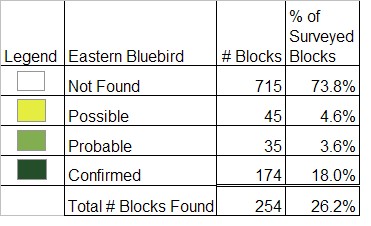

Map Legend and Data Summary

Atlas 1 data collected from 1975-1979

Note: uncommon in open areas and farmland where appropriate nesting cavities or artificial nest boxes occur

Lillian Lund Files