The Unfolding Fern Story

April 01, 2018

Ferns are noted for their beautiful, lacy foliage on the forest floor, but there is a lot more to say about this interesting group of plants than their famous greenery. Fossil records indicate that ferns have been on Earth for more than 360 million years, predating all other groups of plants except the club mosses.

Although their dominance within our forest communities has long been surpassed by conifers and flowering plants, ferns still thrive in our woods and wetlands as major components of the understory.

Parts of the Fern

Their lacy leaves are called fronds. These can be divided into leaflets called pinnae (singular: pinna). The pinna can be even further divided into pinnules.

Spreading Spores

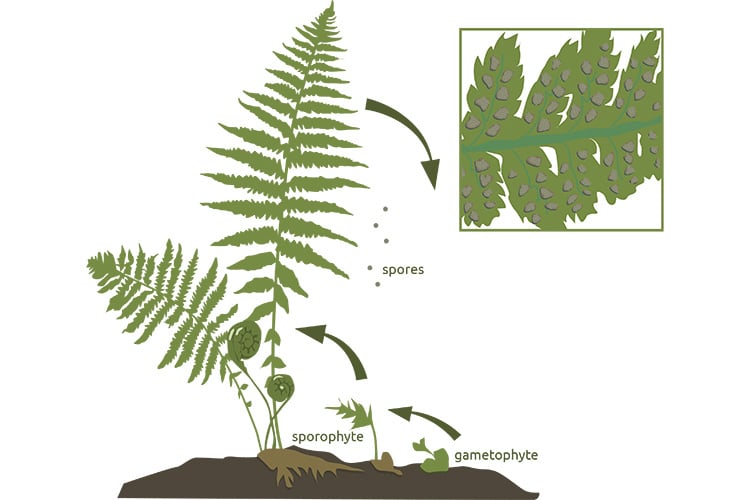

Ferns do not produce seeds, but instead reproduce by means of spores, tiny cells capable of forming a new individual without going through sexual reproduction. Spores have none of the protective coverings and nutritional components that are characteristic of seeds.

Without this extra baggage, fern spores are very light, allowing the wind to carry them long distances. In fact, ferns were one of the first plants to recolonize Mount St. Helens after its eruption in 1980, and that included a species that somehow drifted in from Japan.

Spores are located in clusters called sori (a singular cluster is a sorus). In most species of ferns, you can find these as small dots on the undersides of leaves. If you look at a sorus with a magnifying glass, you will notice that, in some species, a membrane called an indusium (plural: indusia) covers it. The shapes of sori and indusia are often keys to the identification of a species.

Alternate Lifestyle

When a spore germinates, it does not turn into a familiar fern. Rather, it forms a tiny, flat—often heart-shaped—moss-like plant called a gametophyte, which occurs in a type of life cycle known as alternation of generations.

The gametophyte then produces the gametes—the sperm and the egg—which come together to give rise to the fern with which we are all familiar.

Before You Forage

Most ferns unfold in the spring in an artistic “fiddlehead,” a curved structure that resembles the scroll of a violin. The fiddlehead of the ostrich fern—one of our largest fern species—is typically the one folks forage for in the wild or find for sale at farmer's markets in the spring.

But beware—not all fiddleheads are edible, and some, such as the bracken fern, can be toxic.

One of Massachusetts’s most common ferns, the bracken fern typically produces three branches and defies what we usually expect of ferns by growing in sunny locations. Some varieties of bracken produce cyanide and many produce high levels of tannins, which are difficult to digest in large amounts.

Finding Ferns

Massachusetts is a great place to see a diversity of ferns; on Mass Audubon’s wildlife sanctuaries alone, 54 species of ferns have been recorded!

The greatest diversity of ferns occurs in the western part of the state. At Pleasant Valley in Lenox, you can find 40 species, including those that thrive in limestone-rich soil, such as walking fern, adder’s tongue fern, and a variety of grape ferns.

Throughout the state, you can find the beautiful, lacy, and “thrice cut” hay-scented fern, which was a favorite of naturalist Henry David Thoreau. This fern occupies sunny openings in a forest and smells like cut grass in the fall when it dries out.

Another fern favorite is sensitive fern, so called because it is one of the first to succumb to cold in the fall. It does not produce its spores below its leaves, instead producing them on a separate, visually striking stalk that’s often used in floral arrangements.

Finally, there is rock fern (also called Virginia polypody). As its name implies, this fern grows on boulders with very little soil. It is evergreen, so it provides a nice bit of deep-green color even on the coldest winter day.

More to Explore

This spring, practice your fern identification skills at a wildlife sanctuary near you!