Butterfly Atlas

Find a Butterfly

Milbert's Tortoiseshell

Nymphalis milberti

Named

Aglais, Godart, 1819

Identification

Wingspan: 1 3/4-2". Unmistakable. Broad orange and yellow bordering band on all upperwings is unique. Underwings dark brown basally, with wide tan marginal band.

Distribution

Southeastern Alaska east to Newfoundland; south in West to Mexican border, in East to Missouri and West Virginia. Common in northern New England; uncommon to rare southward.

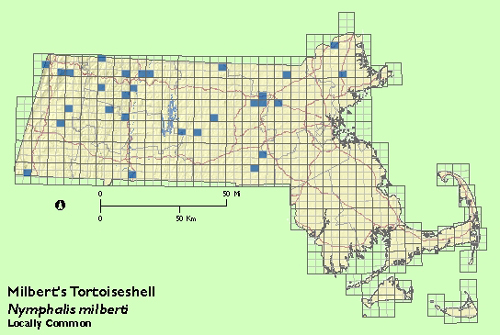

Status in Massachusetts

The Milbert‘s Tortoiseshell is essentially a northern species, usually limited in Massachusetts to higher elevations in the western and northern parts of the state. Scudder knew of few eastern Massachusetts records, but felt it "rather common" in parts of Berkshire county. During the Atlas years, Milbert‘s Tortoiseshell was well distributed in Berkshire, Franklin, and Worcester counties, less so in Middlesex and Essex counties, and scarcely encountered elsewhere, including south central and southeastern Massachusetts.

Usually encountered in small numbers, though R. Busby found the species "numerous" on 15 June 1979 at West Newbury (Essex Co.) (Annual Summary, Lepidopterists‘ Society). Maximum: 6, Whately (Franklin Co.) 2 July 1988.

Flight Period in Massachusetts

Two or three broods. Scudder detailed three broods, as follows:

1. mid June to late July

2. late July to early September

3. a. part of second brood offspring emerges in September, flies in the fall, and hibernates

b. part of second brood offspring pupate in fall, emerges and flies the following spring, March to late May.

Opler and Krizek (1984) say two broods are probably typical, with other appearances resulting from "emergences from summer estivation, as in the Mourning Cloak." Extreme dates: 3 March 1984, Millis (Norfolk Co.) - B. Cassie and "middle of November" Scudder; [latest during recent years: 18 October 1994, Princeton (Worcester Co.), B. Van Dusen.]

Larval Food Plants

Stinging Nettle (Urtica dioica) and Tall Nettle (U. procera) are well documented. Other plants, including willows and sunflowers, have been reported but are probably incorrect.

Adult Food sources

Adults visit a variety of flowers, including Dogbane, Joe Pye Weed, Common Hawkweed, Black eyed Susan, Red Clover, and Common Dandelion. Milbert‘s Tortoiseshells are much more attracted to nectar than are other tortoiseshells. Sap is taken on occasion.

Habitat

Woodland edges and woodland roads; meadows, especially with abundant nectaring plants. Often found in the vicinity of nettles.

Life Cycle

EGG: Pale grass green; barrel shaped, with 9 10 vertical ribs. OVIPOSITION: Eggs laid in "confused heaps, of about three or four layers" (Scudder, 1889), with hundreds of eggs per mass; oviposition on upper half of food plant. LARVA: Blackish, with yellow dorsal and greenish lateral stripes, and black spines. CHRYSALIS: Grayish or greenish tan and thorny. OVERWINTERING STAGE: Adult or chrysalis.

An undetermined percentage of Milbert‘s Tortoiseshells overwinter as adults, and with the first warmth of spring, as early as March, one may see one of these remarkably handsome butterflies on the wing. As the season progresses, and especially during the mid summer flight period, Milbert‘s Tortoiseshells visit meadow flowers and nettle patches, in search of food for themselves and their offspring. The young larvae live communally in a silken nest at the top of the host plant, and feed huddled together on the upper surface of the leaf. The late instar larvae feed separately and rest in a shelter made from a folded leaf. Adults are strong fliers but are not exceedingly wary. In fact, they are usually easily approachable when feeding.

Notes

As noted in Scudder (1889) and Klassen et al (1989), the larvae of Milbert‘s tortoiseshell are greatly affected by parasitic wasps, and apparently only a small percentage survive to adulthood. Westwood recorded a 90% parasitism rate in Manitoba and Scudder found up to 80% parasitism in his autumn sampling. The abundance of this butterfly is said, by Pyle (1981), to fluctuate radically, and this may be due, at least in part, to fluctuations in populations of its larval parasites.

Account Author

Brian Cassie