Find a Butterfly

Regal Fritillary

Speyeria idalia

Named

Drury, 1773

Identification

Wingspan: 2 5/8 - 3 5/8". One of our most spectacular butterflies and difficult to confuse with any other species. The combination of orange forewings and dark purplish, boldly spotted hind wings is unique in our fauna. In our other large fritillaries the fore and hind wings are similarly colored above. The Question Mark with contrasting fore and hind wings lacks conspicuous spotting on the latter and differs markedly in shape, behavior, and habitat. From a great distance superficially resembles other large fritillaries and even Monarch.

Distribution

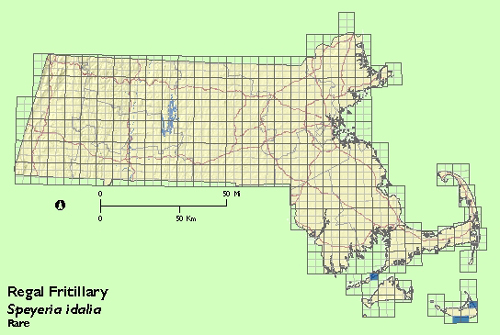

Central eastern North America from eastern Montana, Wyoming, and Colorado east across the Great Plains to New Brunswick and south in the highlands to North Carolina. In New England, Scudder (1889) located idalia‘s northern and easternmost point of distribution as Waterville, Maine, and from this latitude it once ranged south locally throughout the region. Now extirpated from New England.

Status in Massachusetts

Scudder (1889) wrote that the Regal Fritillary "generally speaking is not a common insect". By this he apparently meant that it was local in distribution, since he reported it "quite common" in Springfield (Mass.) and "tolerably abundant ...in Berkshire County, on Cape Cod and, particularly, on the island of Nantucket." He also called it abundant in Connecticut and noted its presence "about Boston." The species has declined precipitously in this century. Writing in the early 1940‘s, Kimball and Jones (1943) found the species still to be "well distributed and common" on Nantucket and "frequent" on Martha‘s Vineyard. As late as the early 1970‘s, idalia could still be found on these islands in suitable habitat without difficulty though it could no longer be described as frequent. During the Atlas period (1986-90), it was seen by reliable observers in small numbers on Nantucket, Martha‘s Vineyard, Naushon (Elizabeth Islands), and Nomans Land. Maxima:?. During the 1980‘s its strongest population may have survived Block Island, Rhode Island, but this too has died out. In the East, mainland populations of the Regal Fritillary, are now known only from Pennsylvania and West Virginia. Midwestern populations also seem to be in trouble, and the species is being considered for inclusion on the Federal Endangered Species List. The causes of this alarming decline remain unclear. Habitat destruction, changes in land management practices, alien insect parasites, pesticides, or perhaps a combination of stresses may be implicated, but corroborative evidence for any is almost nil.

Flight Period in Massachusetts

Formerly from late June (much later on the islands) to the third week in September, peaking from mid-July to early September when both males and females are on the wing. Atlas records ranged from 29 July 1988, Naushon, (Dukes or Barnstable Co.) M. Mello to 18 August 1986, Siasconset, Nantucket, W. Maple. Extreme dates: 25 June, Scudder, no other data; "end of the third week of September in the North", Scudder.

Larval Food Plants

Violets. The main host species in the island populations of southern New England seem to be Ovate-leaved Violet (V. fimbriatula) and Lance-leaved Violet (V. lanceolata), a common wet meadow species. (cit. Schweitzer papers). (In the Mid west Idalia favors Bird‘s Foot Violet (Viola pedata), but apparently did not use this species on the sand plains of Nantucket and Martha‘s Vineyard where it is common.

Adult Food sources

Visits a variety of mid- to late summer wildflowers: Common and Swamp Milkweeds, Butterfly Weed ironweeds, bonesets, thistles, goldenrods, asters and Red Clover are frequently cited; Schweitzer (cit =pers comm from notes or in papers) notes a strong preference for Northern Blazing Star (Liatris borealis), a fire dependent species rare in southern New England.

Habitat

In Massachusetts Regal Fritillary seems to have preferred extensive open areas with a combination of wetlands and upland fields containing an abundance of nectaring plants. In the Midwest -- where it is also in marked decline -- it is a characteristic species of the tall grass prairie, but has also been recorded from cow pastures, mountain meadows, marshes, and grassy bogs. As it dwindled on Martha‘s Vineyard, it survived longest in the prairie-like Katama Plains.

Life Cycle

EGG: Pale green when laid becoming purplish brown; dome-shaped with an open top, 16-18 vertical ribs, many finer lateral ribs covered with tiny punctures. OVIPOSITION: Eggs are laid on or near the foodplant from late August to mid-September; eggs hatch in three to four weeks. LARVA: The mature larva is black (invariably described as "velvety") with yellow markings turning reddish and covered with bristly spines. Emerging from its winter dormancy in spring the young larva begins to eat violet leaves, feeding at night and resting away from the host plant by day; the first instar larva enters diapause in a sheltered spot immediately, eating nothing except its eggshell. CHRYSALIS: Brown, yellow and pink with blackish spotting and rows of blackish tubercles down the front. PUPATION: Occurs mainly in June and takes about 17 days; chrysalis is suspended head downward by a silk holdfast. OVERWINTERING STAGE: First instar larva.

Males emerge first beginning in late June; females normally do not appear until the end of July and continue emerging until the third week in August. The courtship ritual, similar to the other Speyerias, is described in detail by Clark (1932).

Many observers have described this butterfly‘s habit of flying three to four feet above a field and then suddenly dropping "like lead". Females that do this have been seen to walk on the ground for 10-15 minutes laying their eggs on any handy plant, leaving the "infant" larva to find its own violets - which are invariably nearby.

Account Author

Chris Leahy