Find a Butterfly

Great Spangled Fritillary

Speyeria cybele

Named

Fabricius, 1775

Identification

Wingspan: 2 1/8 - 3". Three of the large New England fritillaries - Great Spangled, Aphrodite and Atlantis - are superficially quite similar. With practice, however, they are readily distinguishable in our area in most cases by noting a combination of field marks, as follows:

1. Size: Great Spangled is the largest of the three species and Atlantis the smallest with Aphrodite falling between the two extremes. The size difference is very obvious when comparing Great Spangled with Atlantis, but Aphrodite‘s measurements overlap in both directions. Females of all species tend to be larger than males, so that the largest female Aphrodite can be as large or larger than the smallest male Great Spangled and the largest female Atlantis can be as large or larger than the smallest male Aphrodite. If you compare males to males and females to females by measuring the forewings from base to tip, there is no overlap in most cases as shown in the table below. See below for other differences between males and females.

Length of Forewing (base to tip) in Centimeters*

| Range | Males and Females | Males | Females |

| Great Spangled | 3.5 - 4.7 | 3.5 - 4.0 | 4.2 -4.7 |

| Aphrodite | 3.1 - 4.0 | 3.1 - 3.4 | 3.7 - 4.0 |

| Atlantis | 2.7 - 3.3 | 2.7 - 3.3 | 2.8 - 3.3 |

* Derived from Opler and Krizek, 1984

2. Hindwing Pattern Below: Great Spangled has a relatively wide (submarginal) yellow band between two parallel rows of large silver spots; this band is much narrower in Aphrodite and very narrow in Atlantis. In both Aphrodite and Atlantis, the large silver spots of the inner row are tipped with small brown "pom-poms" that are absent in Great Spangled.

3. Forewing Basal Mark: Males of Aphrodite and Atlantis usually have a small black mark near the hind margin of the forewing above, about a third of the way out from the body toward the wing edge. This spot is lacking in Great Spangled.

4. Marginal Lines: All three species have narrow black "railroad tracks" along the margins of both wings above and below. In Atlantis, the double line merges or nearly so, giving the impression of a single heavy black border.

5. General Coloration: Great Spangled tends to look less reddish than the other two, and Atlantis generally appears very dark. However, light, individual variation, and wear can all affect color and our perception of it, making it the least reliable of characters.

Among these species, females tend to be darker than males with heavier, "smudgier" black markings, further confusing color distinctions. They also tend to be less orange in ground color, more "brassy".

6. Range: Atlantis is a northern and mountain species and is therefore absent from much of eastern and southern New England leaving only two look-alikes to distinguish.

Distribution

Across North America from eastern British Colombia, coastal Washington and Oregon and central California (in the mountains) east through the northern prairies and Great Plains to Nova Scotia and south in the highlands to northern Georgia and Alabama. Absent from Texas and the Gulf and Atlantic coastal plains. Throughout New England; less common northward.

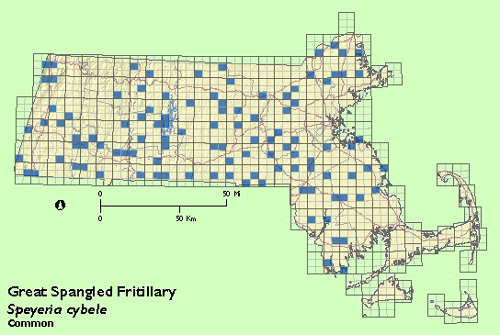

Status in Massachusetts

Scudder (1889) considered the Great Spangled Fritillary to be "uncommon...in the northern half of New England...but in its extreme south exceedingly abundant." Today the species remains common, though by no means abundant, throughout much of the state. During the atlas period it was not taken from Cape Ann, Cape Cod or the Islands and appears to have been always rare or absent from these eastern extremities. A number of collectors who have worked in Massachusetts for many years agree that this species has declined significantly during the last half century. Maximum : 93, Prescott (Hampshire Co.), 19 July 1994.

Flight Period in Massachusetts

A single flight period with most individuals on the wing from the last week in June to the first week in September. Extreme dates: 29 April 1986, Millis (Norfolk Co.), sight record B. Cassie; 16 June c. 1880‘s, "latitude of Boston," S. Scudder; 24 June 1987, Bridgewater (Plymouth Co.), K. Holmes; 23 September 1989, Gilbertsville (Worcester Co.), G. Davis; 8 October 1995 Newbury (Essex Co.), S. Stichter.

Larval Food Plants

Violets. Edwards claimed to have fed this species on "every species of wild violet accessible from the woods, and during the winter cultivated species, and discovered no preference for one more than another." Yet the literature contains relatively little on which species the fritillaries actually use in the wild. Furthermore, in Massachusetts these butterflies appear to be largely absent from the sandy coastal plain and islands where Bird‘s Foot Violet (Viola pedata) and several other species are abundant. Massachusetts violets apparently known to be used in the wild are: Common Blue Violet (Viola papillionacea), common in wet meadows and moist woods; Canada Violet (V. canadensis), rich woods; Sand Violet (V. adunca), listed as Endangered in Massachusetts; and Round-leaved Violet (V. rotundifolia), a yellow, rich woods species.

Adult Food sources

Nectars avidly on milkweeds, thistles, Joe-Pye-Weed and other composites, Red Clover, Alfalfa, and various vetches; plus dogbanes and many other common midsummer wildflowers. Also visits cultivated gardens frequently. Recorded nectaring on 26 species during the Atlas period.

Habitat

Frequently associated with wet meadows and weedy upland fields, usually near woods (where several of its reported host violets occur). Wanders widely to gardens and even bogs (Clark and Clark, 1951).

Life Cycle

EGG: Honey yellow to tan; dome-shaped with 16-18 vertical ribs and finer lateral ribs and a surface texture of wavy lines and tiny depressions. OVIPOSITION: The eggs are not laid until late August and early September, and are deposited singly on or near violets; they hatch in two to three weeks. LARVA: The mature larva is black and covered in bristly spines. The first instar larva eats part of its eggshell and then seeks shelter in leaf litter or other insulated retreat where it enters diapause without feeding further. It emerges in the spring with the first growth of violets in May and begins to feed, mainly on the leaves but also on the flowers if available. It feeds only at night and conceals itself in litter away from the food plant by day. CHRYSALIS: Glossy brown (sometimes dark or reddish) blotched with black; prominent abdominal spines (tubercles) mainly black, some yellow. PUPATION: Occurs in June and lasts from two to three weeks; the chrysalis is suspended head downward by a silken holdfast (cremaster) attached under a rock,log or bark. OVERWINTERING STAGE: First instar larva.

In Massachusetts, males emerge in late June or earlier. They are very active and may patrol regular circular beats around chosen open habitats in search of females, but also travel widely. Females begin emerging in early July. Male courtship display involves opening and closing their wings towards the females probably as a means of transferring their pheromone. According to Scudder (1889), pairing mainly occurs at the end of July. Egg laying routinely continues into September.

Account Author

Chris Leahy