Find a Butterfly

Eastern/Canadian Tiger Swallowtail

Papilio glaucus/Papilio canadensis

Named

Linnaeus, 1758

Taxonomy & Nomenclature

Note: Eastern and Canadian Tiger Swallowtails are now two separate species, but at the time of the Atlas and the following species account, canadensis was considered a subspecies of glaucus.

Identification

Wingspan: 47-58 mm. (see footnote*) The Tiger Swallowtail, including its northern subspecies, the Canadian Tiger Swallowtail, is the only large yellow butterfly in New England with vertical black stripes, and tails on the hind wings. The "regular" Tiger Swallowtail is distinguished by a row of yellow spots paralleling the black border of the outer edge of the under surface of the forewing. In the Canadian Tiger Swallowtail subspecies, (P. glaucus canadensis, Rothschild & Jordan 1906), instead of the row of yellow spots, there is an unbroken yellow band. Because Massachusetts sits astride the transition zone between the ranges of these two entities, distinctions are difficult: many transitional individuals have the upper part of the forewing row of yellow spots fused into a yellow band, and these individuals are often the largest of the Massachusetts "Tigers." The black southern form is more southern and is not to be expected in Massachusetts.

Distribution

Alaska through Canada to the Maritimes, and east of the continental divide to the Gulf coast and southern Florida. Glaucus south in the mountains - E. Sierra Madre - to Veracruz. In the northern part of the range, including some of the more northern counties and higher elevations in Massachusetts, the Tiger Swallowtail gives way to the Canadian Tiger Swallowtail subspecies.

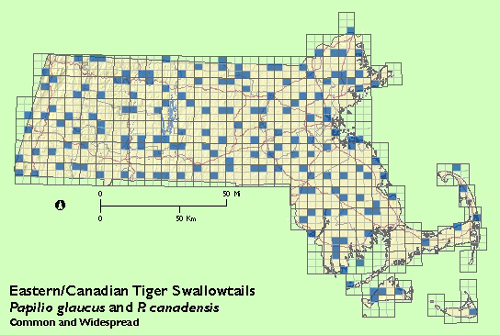

Status in Massachusetts

Common and widespread. Maximum: 81, Greylock (Berkshire Co.), T. Dodd.

Flight Period in Massachusetts

Beginning of June, peaking in early July, and tapering off through August and into very early September. The peak flight seems to coincide with the blossoming of the common milkweed, and the Atlas observations do not give clear evidence of a second flight peak later in the summer. In Connecticut and further south there are clearly two flight periods, the first coinciding with lilac blooming.

The Canadian Tiger Swallowtail subspecies (P. glaucus canadensis, Rothschild & Jordan 1906) has an earlier flight period, beginning in early May and peaking at lilac time. North of Massachusetts the flight tapers off in early July. Here, as indicated by Atlas specimens, transitional individuals are observed well into August. It is possible that some of these represent a second flight.

Larval Food Plants

Wild cherry and ash are commonly used, and sometimes lilac and spice-bush. Where tulip poplar occurs naturally, as in Connecticut and southward, it is a primary food plant. As one goes farther north in New England, where only subspecies canadensis occurs, aspen and birch are regularly used, along with cherries and ash where available; but canadensis cannot survive on tulip poplar.

Adult Food sources

A wide variety of wild and garden flowers, limited mainly by the ability of the blossom to support the weight of the butterfly. It will clamber into the deep throat of the day lily for nectar, or bend the delicate stem of the Canada Hawkweed nearly to the ground. Males may congregate by the dozens ("puddle clubs") on patches of damp sand or soil, particularly if it has been enriched by urine, campfire drippings, or seepage from carrion. Dead fish are often the focus of such aggregations. Tiger Swallowtails have even been seen feeding on the remains of roadkill butterflies!

Habitat

Because appropriate larval host plant hardwoods and suitable nectaring plants are so ubiquitously distributed throughout our area, the butterfly is well known everywhere. They are most readily observed at nectar sources, at puddling sites, and as the males patrol fields and roadsides.

Life Cycle

Tiger Swallowtails eclose from the overwintering pupa from early May into early summer, the subspecies canadensis accounting for the earlier Massachusetts observations. When seeking mates, males patrol a "beat" around the edges of a field or wood or along a forest road and may reappear at intervals of 15 to 20 minutes on the same route and in the same direction. Mated females place semi-spherical green eggs singly on the upper surface of the leaf, commonly on branch tips high in the host plant tree, but also on lower second growth. In the first three stages and the early part of the fourth, the larva is a "bird dropping" mimic, a wet-looking mixture of black, brown, olive and white which rests on a thin silk mat on the upper leaf surface and feeds from a different part of the leaf or from an adjacent leaf, day or night. In the later stages the silk mat is engineered so as to curl the leaf into a concealing tube-like shelter, and inclined so that droppings will roll out and leave the shelter clean. In the latter part of the fourth stage, green becomes the predominant larval color, while in the last stage, it is all a deep "forest green," with moderate sized eye-like spots on each side of the humped thorax, and a belt-like narrow yellow band between the first and second segments of the abdomen. A forked orange osmaterium, exuding a fruity odor, can be extruded from the front of the thorax when the larva is disturbed. The mature larva turns a dirty yellowish brown when it begins to wander in search of the pupation site. There, it hangs up beneath a supporting twig or curl of bark, and, attached by a silk pad at its posterior end and a silk "seat belt" behind the thorax, transforms into the brown and gray pupa. Emergence is in about two weeks if there is to be a second flight, or else after hibernation, depending on latitude and subspecies.

Notes

The differences between the Canadian and Tiger Swallowtail are presented here to cast light on the otherwise puzzling situation, that the butterfly should have its flight peak earlier in the year in northern New England than in parts of Massachusetts where spring comes sooner.

________

* Observations on forewing length from MBAP glaucus specimens through 1988.

This account was contributed by William D. Winter.

Account Author

William D. Winter