Find a Butterfly

Monarch

Danaus plexippus

Named

Linneus, 1758

Identification

Wingspan: 3 1/2 4". This familiar large, orange butterfly with prominent black veins and borders can only be confused with the Viceroy (Limenitis archippus). According to Opler (1992) the wingspan of the Viceroy ranges between 67 and 84 mm while the Monarch‘s wingspan is between 86 and 125 mm. The Monarch lacks the characteristic bold black line crossing the hindwing of the Viceroy. Male Monarchs have a black "scent patch" located centrally on the hindwing that appears as an enlarged area on one of the main veins.

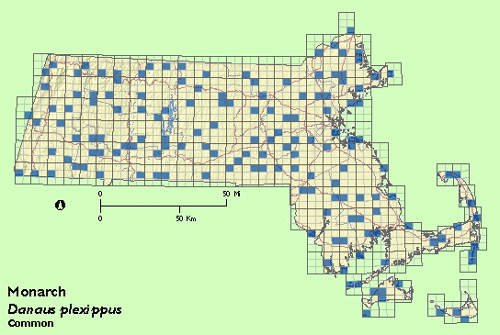

Distribution

In the Americas from southern Canada south to Argentina. Resident populations in New World tropics and Bahamas south through the Antilles. Summer resident throughout the lower 48 with wintering population in southern Florida, Texas, California, and central Mexico. Migrants are seen throughout New England. Introduced and well established in Australia, Hawaii, and the Pacific basin. While Monarchs seem to be maintaining adequate populations within their breeding range, there is cause for great concern over the continuing destruction of their coniferus forest wintering habitat in Mexico. Air pollution and habitat destruction may also endanger this butterfly‘s legendary migration.

Status in Massachusetts

A common summer butterfly in most areas of the state from the western border to the Cape and islands; a common to abundant migrant along major river valleys and the Atlantic coast. In Massachusetts, from mid-August through late September and early October, Monarchs can be observed moving southward. Aggregations are most regularly seen along the coast as well as in association with other leading lines such as river valleys and ridgelines. While each Monarch is an independent traveler, congregations are regularly observed especially at the coast and on cold nights at communal roosts. Migrants display highly directional flight when winds are favorable. Under adverse conditions, such as strong southwesterly winds, the migrants may often be found nectaring or just "hunkered down" awaiting a change in the weather. Maxima: regularly occurs in large concentrations at Eastern Point, Gloucester (Essex Co.), as 2000+ on 13 September 1994.

Flight Period in Massachusetts

Two to four flights from mid June through September. Extreme dates: 16 April 1994, Boston (Suffolk Co.), R. Stymeist and 4 December 1994, Nahant (Essex Co.), S. Zendeh and Falmouth (Barnstable Co.), G. Martin.

Larval Food Plants

Milkweeds including Common Milkweed (Asclepias syriaca) and Swamp Milkweed (A. incarnata).

Adult Food sources

Visits a wide variety of flowers: thirty three flower species noted during Atlas period, including many asters and goldenrods.

Habitat

Open meadows, fields, and wetland edges especially areas with milkweed. On migration virtually anywhere with concentrations noted along ridge lines, river valleys, and coast lines.

Life Cycle

EGG: White; dome shaped. OVIPOSITION: eggs usually laid singly, usually on underside of host plant. LARVA: Black and yellow with bold white bands. CHRYSALIS: Jade green waxy surface bespeckled with gold. OVERWINTERING STAGE: Does not overwinter in any stage in New England; adults winter in communal roosts to the south. The extent to which the Monarch has been researched and written about has resulted in it becoming one of the best known insects (see also Notes below). Our only true two-way migrant butterfly, details of its spectacular flights and Mexican wintering sites of the North American populations east of the Rocky Mountains were first revealed by Urquhart (1976). Malcolm et al (1991) subsequently elucidated the specifics of remigration strategies that bring the first flight of Monarchs back into North America in early Spring and ultimately to our area in late May and June. Several generations of Monarchs occur in Massachusetts each season. Adults of the summer broods are on the wing for approximately three weeks while the final, late summer flight of migratory individuals may survive for up to nine months during which time they migrate to the central Mexican highlands and overwinter at several sites in the Transvolcanic Mountains. In March these same individuals begin the northward migration, normally reaching only the southern regions of North America, where they produce the next generation of Monarchs that will continue the migration northward.

Notes

The Monarch is one of the few insects that has caught the fancy of the general public. Along with its migration, the Monarch‘s story includes fascinating details of predator defense. As caterpillars, Monarch‘s feed on milkweed plants (Asclepias spp.). Some milkweed species contain heart poisons (cardiac glycosides). This toxic chemical, when ingested, is sequestered by the caterpillar and passed on to the adult butterfly. Experiments have shown that birds attempting to feed on these toxic butterflies react by vomiting and soon learn to avoid this prey. Different populations of Monarchs have varying amounts of poison due to the specific larval hostplant on which they feed. The story of the Monarch also includes its relationship with the Viceroy (Limenitis archippus). Traditionally the Monarch was seen as the model and the Viceroy as the mimic in a classic Batesian relationship in which a non-toxic species gained protection by its look alike adaptations. Recent research, however, suggests that both the Monarch and the Viceroy may be toxic (see, Viceroy account). The public‘s fascination with the Monarch reaches its height in Pacific Grove, California. Here, at the well-known wintering sites of the western North American populations of Monarchs, the town celebrates this insect with an annual parade. Naturalists interested in the Mexican wintering sites of the eastern population now take advantage of a small industry that enables tourists to visit a select few of the wintering sites in Mexico. Efforts are underway in the United States and Mexico, notably the Monarch Project of the Xerces Society, to further educate the general public about monarch biology and conserve such wintering sites. Recently the Entomological Society of America has launched a campaign whose goal is to have Congress designate the Monarch as our national insect.

Account Author

Richard K. Walton