Find a Butterfly

Cabbage White

Pieris rapae

Named

Linnaeus, 1758

Identification

Wingspan: 1 1/4 - 1 7/8". This is the common white butterfly of Massachusetts and the only one to be expected in the eastern half of the state. Cabbage White can be distinguished from the two other whites found in western Massachusetts by its dusky forewing tips and lack of dark scales below. Upper surfaces white with charcoal forewing tips; black spots, one in male / two in female, on forewings. Ventral hindwing and forewing tips pale yellowish green. Black markings and yellowish tinge reduced or absent in spring broods.

Distribution

Throughout the United States except for portions of central and southern Texas, southern California, and Arizona. Northward to central Canada. In New England, absent only in northern Maine.

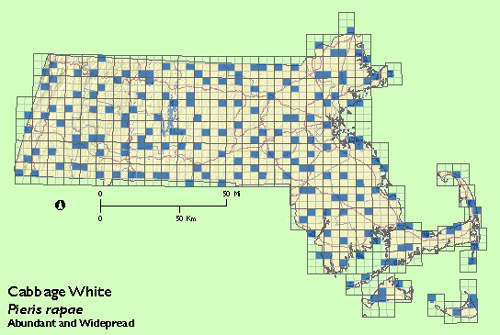

Status in Massachusetts

Abundant and widespread. This Eurasian species was introduced in Quebec City in 1860 and in New York in 1868. The species was widespread in New England by 1871. During the Atlas Project this butterfly was recorded in virtually all of the quadrangles. Maxima: 600+, Gooseberry Neck, Westport (Bristol Co.), 12 September 1993.

Flight Period in Massachusetts

Three or more flights. Generally on the wing from late April to late September; Extreme dates: 1 March 1991, Needham (Norfolk Co.), D. DeWolf and L. White and 3 December 1994, Long Island, Quincy (Norfolk Co.) P. O‘Neill.

Larval Food Plants

Numerous crucifers including Brassica species, cresses (Barbara spp.), and peppergrasses (Lepidium spp.) as well as cultivated cabbage and other mustards.

Adult Food sources

62 species noted during Atlas project.

Habitat

Widespread in cultivated areas, especially agricultural and residential gardens; also weed fields, meadows, and occasionally open woodlands.

Life Cycle

EGG: Yellowish green to white, spindle shaped with several vertical ridges. OVIPOSITION: Eggs laid singly (clusters reported in England) on underside of host plant. LARVA: green with yellow lines along the back (solid) and sides (broken). Larvae may feed by boring into cabbage plants and thus cause extensive agricultural damage. CHRYSALIS: Greenish or tan with numerous speckles; angular; attached at base and supported by silk girdle. OVERWINTERING STAGE: Chrysalis

In Massachusetts, Cabbage Whites are on the wing from early spring to late fall. Early and mid summer broods complete the process of metamorphosis from egg to adult in approximately 5 weeks. The final, late summer generation completes the larval stage.

Notes

Scudder (1889) noted that after its introduction, the Cabbage White had spread south to Florida and west to Colorado by 1886. Scudder was convinced that this introduced species had adversely affected at least one native population of butterfly, the Veined White (Pieris napi, formerly P. oleracea). "The story of the abundance and probably the distribution of P. oleracea would now be a very different one, for the invader has nearly exterminated the indigenous species. I recollect once seeing the college yard in Cambridge, I think it was about 1857, fairly swarming with P. oleracea. It is now never found to my knowledge anywhere in the region about Boston . . ." Recent opinion, however, points to human induced habitat changes as a partial, if not exclusive, cause for the replacement of P. napi by P. rapae (Chew, 1977; Pyle, 1981).

Scudder also pointed out that, within a quarter century of its arrival in this country, rapid and widespread colonization of rapae had resulted in massive crop losses, mainly to cabbage. Attempts to control or eradicate the Cabbage White have led to a series of biological fiascoes. The disastrous consequences of the widespread use of chlorinated hydrocarbons including D.D.T., during the period following World War II, is well documented. Of late, a more "enlightened" approach has employed the use of biological controls using other organisms, often exotic, introduced species, to parasitize or otherwise prey on the pest organism. Unfortunately, such biocontrols have tended to cause more problems than they have solved and have as Howarth (1983) points out "involved significant negative impacts on agriculture, native ecosystems, and human health."

Account Author

Richard K. Walton