Fireflies

Also known as "lightning bugs," fireflies are neither bugs nor flies—they are actually beetles that light up using a chemical reaction in their lower abdomen (the bottom part of their body). Some of them light up in a specific blinking pattern, like a secret code that they use to “talk” with other fireflies and to find mates.

All fireflies belong to the same beetle family, although three groups have different ways of attracting mates. Some fireflies make quick flashes, while other fireflies give long-lasting glows, and still others use invisible chemical signals.

Types of Flashing Fireflies

In North America, there are over 150 species of fireflies in 16 genera. There are three main groups of flashing fireflies: Photinus, Pyractomena, and Photuris.

These fireflies are very difficult to tell apart, and researchers are not yet sure how many different species live in New England!

Photinus

Photinus fireflies tend to be small, about one half inch in length.

Approximately 15 species of this family of firefly live in New England.

They produce a yellow-green flash and can be active at dusk or at night.

Pyractomena

Pyractomena fireflies can be distinguished by the raised ridge that runs down the middle of their pronotum (head shield).

They are about the same size as Photinus, but their flashes are often amber colored, like an ember flickering from a campfire.

They are mainly active at night.

Photuris

Photuris fireflies are big (up to an inch long), active, and have long, slender legs.

They looked hunched around their shoulders, and often have light stripe running diagonally down their elytra (wing covers).

Flashes of Photuris species are noticeably greener and brighter compared to those in the Photinus family.

Behavior

Since they’re so conspicuous, it seems like fireflies would be an easy target for predators. But they’re not as defenseless as they might appear!

When attacked by a predator, fireflies release tiny drops of blood containing distasteful, toxic chemicals. Studies have shown that predators like birds, toads, and even some spiders quickly learn to steer clear of fireflies. In fact, it is thought that firefly bioluminescence first evolved to ward off potential predators—this bright warning originally meant “don’t eat me, I’m toxic!”

However, there is one predator that isn't fazed by this defense mechanism—Photuris firefly species, who actually prey on other fireflies! The females imitate the response flashes used by Photinus females. A male Photinus firefly may see this flash and approach with mating on his mind. When he gets close enough, the Photuris female will seize and eat him.

The predatory Photuris fireflies are unable to make their own defensive chemicals. By consuming other fireflies and hijacking their toxins, Photuris is able to gain protection from their own enemies.

Life Cycle

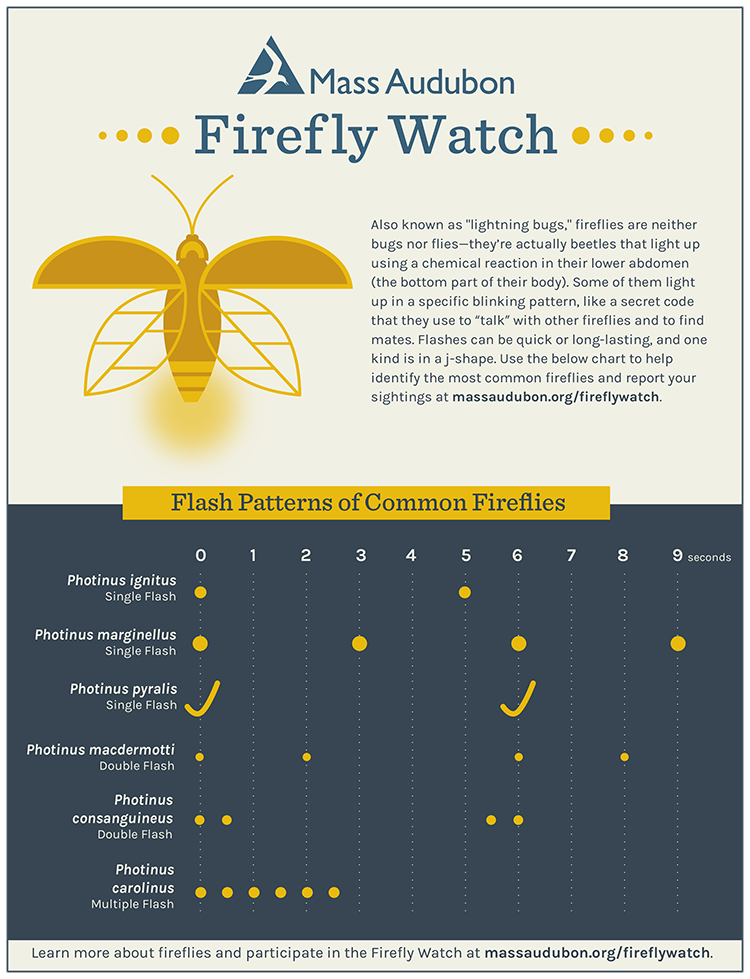

Bioluminescent fireflies are unusual in their ability to produce light, enabling them to attract mates using signals that are highly visible even in the dark. Many firefly species give distinctive flash patterns that differ in their flash color, the number and duration of flashes, and the time in-between flashes.

In North America, male fireflies seek mates by flying around and flashing. Females rest on vegetation and generally do not fly. When a female sees a male of her own species, she answers by flashing back to him. In this way, females choose their mates—if she doesn't respond to a male’s flash, he cannot find her in the dark.

A few days after mating, a female lays her fertilized eggs on or just below the surface of the ground. The eggs hatch three to four weeks later, and the larvae feed until the end of the summer. Fireflies hibernate over winter during the larval stage. Some do this by burrowing underground, while others find places on or under the bark of trees.

The larvae then emerge from hibernation in the spring. After several weeks of feeding, they pupate for 1–2.5 weeks and emerge as adults.

Food

A firefly's diet depends on where it is in the life cycle. As newly emerged larvae in the spring, most fireflies feed on other insects, snails, and worms. As adults, their diet varies from species to species—some are predatory, while others feed on plant pollen or nectar.

Observing Fireflies

There are two ways to observe fireflies:

- From afar by watching their flight paths and flash patterns.

- Up close to determine what type and gender by examining body parts.

Observing From Afar

As you begin to observe the fireflies in your habitat, you will quickly notice that they have different flash patterns. Each species of firefly has its own pattern. Many fireflies look similar, so these flash patterns help to identify particular firefly species.

With a little practice, you can learn to recognize many fireflies by their flash pattern.

If you hope to observe fireflies in action, be careful not to shine flashlights or other bright lights near them. Fireflies communicate using light, so bright lights can disrupt their communication, and interfere with their nightly routine!

You can protect fireflies and still safely see in the dark by using a red flashlight. You can turn any flashlight red by taping a few layers of red acetate (available at most art supply stores). Use this flashlight to get to your firefly habitat—but once you find fireflies, turn it off and let the insects take care of the lighting!

If you let your eyes adjust to the dark, their display will appear even more beautiful.

Note: Be on the lookout for ticks and wear insect repellent!

Up-Close Observation

There are three major kinds of flashing fireflies in North America, and you can tell them apart by looking closely. You can also tell the sex of a firefly by examining its brightly glowing lantern.

To do this, place the firefly so you can see the underside of its abdomen. The lantern covers the last one or two abdominal segments. Male lanterns are larger, covering two whole segments. Female lanterns are smaller and cover just a small part of one or sometimes two segments.

The best way to observe a firefly up close is to capture it in a net and place it gently into a clear box.

To avoid harming a firefly, collect it with a net. Then gently place it in a jar containing a moist paper towel for humidity. After you’ve gotten a good look, remember to let your fireflies go where you found them.

If you handle fireflies, make sure you don’t have any insect repellent on your hands, and wash your hands carefully when you’re done.

Report Your Sightings

Join a network of volunteers by observing your own backyard and help scientists map fireflies found in New England and beyond as part of Firefly Watch. Learn more about Firefly Watch

Stay Connected

Don't miss a beat on all the ways you can get outdoors, celebrate nature, and get involved.